Siddique Kappen Case: A Betrayal of Justice

Nine months on, the Hathras rape case is itself almost forgotten and even the UP government’s abject failure in dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic has receded from national headlines. Will there be any justice for journalist Siddique Kappen, who awaits a plea for bail to come up before a court in Mathura, asks N P Chekkutty.

This week, Siddique Kappen, a 42-year-old journalist from Kerala who worked at the national capital for over eight years, enters his ninth month in captivity of the Uttar Pradesh police in a case that can only be described as Kafkaesque. He was taken into custody by the UP police on October 5, 2020, at a traffic junction on the national highway as he was travelling to Hathras, to report on an incident that had captured national headlines. Kappen was a journalist working for a small website in Malayalam on a retainership and his finances were so strained that he was scouting for a vehicle to travel to Hathras and had hitched a ride in a car that had been hired by two student activists from the Campus Front of India, with whom he had got acquainted during his work as a journalist.

He was not allowed to contact his friends in Delhi, where he was a member of the Press Club of India and also an office-bearer of the Delhi unit of the Kerala Union of Working Journalists (KUWJ). He was also not allowed to contact his family at Vengara, a village in Malappuram in north Kerala.

Since Kappen was not able to contact his family and friends, his worried colleagues in Delhi filed a habeas corpus case in the Supreme Court. His lawyer Wills Mathew travelled to meet him in Mathura where Kappen was lodged in a temporary jail. However, Mathew was not allowed to talk to him. The Supreme Court heard the plea of senior counsel Kapil Sibal, appearing for the KUWJ, and ordered the police to make arrangements for ensuring legal support for him and also daily phone communication with family and his lawyers.

Kappen was first charged with minor offences. Later, the charges were amended and provisions of the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), along with charges under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) and the Information Technology (IT) Act were also imposed on him and the two student activists (Atiq-ur Rehman and Masood Ahmed and Alam, who was driving the vehicle) arrested with him. The charges against him include conspiracy (sec. 120b), sedition (124a), causing friction among various communities (153a) and some sections in the IT Act, etc, linked to an FIR filed on October 4, in which the Adityanath government named many “unnamed persons” as creating a conspiracy to create communal tensions over the Hathras incident and defame the government.

(FSC Note: The charge-sheet in the case, filed by the Uttar Pradesh police’s Special Task Force (STF) on April 4, 2021, lists eight persons besides journalist Siddique Kappan and members of Popular Front of India (PFI) and its student body, Campus Front of India (CFI). They are CFI national general secretary K A Rauf Sherif, CFI national treasurer Atikur Rahman, Delhi CFI general secretary Masud Ahmed, CFI member Mohammed Alam and Anshad Badruddin, Firoz Khan and Danish.

Kappan, a convenient scapegoat?

The sequence of incidents clearly indicates that Siddique Kappen was a victim to the failure of the Adityanath government to ensure justice to the citizens in that state and when criticism was raised, an attempt to cynically shift the responsibility and deflect public attention. The UP police, under severe public scrutiny for their mishandling of the case of the rape and tragic murder of a Dalit girl in the village, seemed to wantonly to shift focus away from them and were looking for scapegoats. The pet theory of Islamist extremists in a conspiracy to defame and destabilise the Adityanath government fit the bill perfectly and they jumped at it when Kappen was detained.

Kappan was harassed and manhandled in police custody for days as they tried to elicit a confession tailored to their convenience, as he later told his wife Raihanath Siddique when, after a Supreme Court intervention, he was allowed to talk to his family back home. They had asked him why Kappen, a Muslim, was interested in the case of a Dalit girl? It was as if the state of Uttar Pradesh under Adityanath rule was out of bounds for Muslims living in India as well as journalists who sought information on human rights violations there.

Supreme Court intervention

The Supreme Court has so far intervened in his case three times. First, to ensure his personal safety and legal support in custody. Second, to release him on a five-day parole early this year to travel to Kerala to meet his 90-year-old mother. The third intervention was to ensure that he received immediate medical treatment in a Delhi hospital when he was known to have contracted Covid-19 in the Mathura jail.

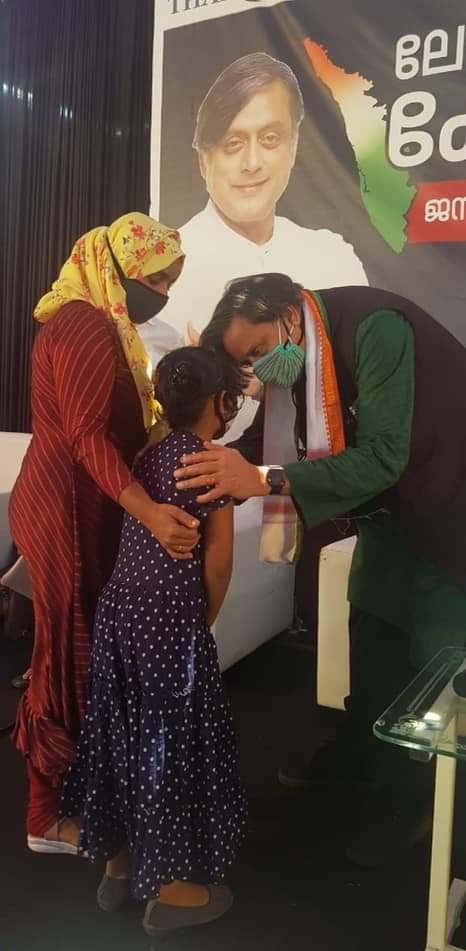

The information about the spread of the disease in the jail was leaked out sometime in April and on April 24, Kappen phoned up to tell his wife that he was admitted to the KM Medical College hospital in Mathura where he was chained to the cot in the Covid ward like an animal and was not being allowed even to go to the toilet. He wanted to be returned to jail and die there as his condition in the hospital was so unbearable, says his wife. She was appalled and her distraught voice mail, sent out to her friends and members of the Sidique Kappen Solidarity Committee, was picked up by mainstream media and there was a public outcry. His wife Raihanath sent a petition to Chief Justice N V Ramana for his urgent intervention to save the life of her husband.

The Kerala chief minister Pinarayi Vijayan, who had hitherto refused to intervene in the case, wrote a letter to UP chief minister Adityanath, asking for urgent steps to ensure proper medical treatment for the Malayali journalist. After four days of this agony in the Mathura hospital, his case was taken up by the Supreme Court which ordered his shifting to the All India Institute of Medical Sciences or some other premier government hospital in Delhi for his treatment. The Solicitor General for Government of India, Tushar Mehta, fiercely opposed it but the bench, led by the chief justice, ruled it out.

Kappen was shifted to Delhi and admitted to AIIMS for three days and then secretly discharged around midnight and moved back to Mathura. His wife Raihanath and elder son had travelled to Delhi in the hope of seeing him at the hospital but were not allowed to do so by the UP police. The police also failed to inform the family or the Supreme Court about his treatment or whether he had recovered from Covid. The family then filed a contempt of court petition in the Supreme Court, alleging that he was discharged by the UP police without his proper recovery in the hospital. They also alleged that he had sustained some injuries on his lower jaw as he fainted in the jail toilet and it was causing problems to him while eating and that no steps were taken to provide treatment for those issues.

Endless wait

The Supreme Court, while disposing of the habeas corpus petition of KUWJ in April, had said that Kappen could approach the lower courts for regular bail. His lawyer, Wills Mathew, filed a bail application in the Mathura court last week with a prayer for a regular bail as his client had spent eight months in jail and that there was no proof for any of the charges levelled against him and that as a senior journalist he was being unlawfully harassed for doing his legitimate duty of upholding the rights of the citizens for free and fair information, without fear or favour. He was a journalist of many years’ standing and was never involved in any cases of a criminal nature.

So now Kappen enters his ninth month of incarceration, waiting for UP courts to hear his plea for bail, even as the weeks and months trickle on with no freedom in sight.

(N P Chekkutty, a senior journalist in Kerala, was a colleague of Siddique Kappen at Thejas Daily, and also heads the Siddique Kappen Solidarity Committee that campaigns for his release).

Related