When hate speech falls short of being free speech

Republished from The Leaflet with permission

Hate speech vitiates the very purpose of free speech, which is the free and fearless operation of a human mind that constantly seeks answers and the truth, says Ujjaini Chatterjee

Contemporary Indian democracy is at a threshold of its constitutionalism. Amidst the deafening noise of the media and a structured, institutionalised, political propaganda of minority marginalisation every second day, there is a renewed debate regarding what constitutes an exercise of the freedom of speech and expression and what are the reasonable and legitimate restrictions that may be imposed on this exercise of free speech.

In the context of the recently-suspended BJP spokesperson, Nupur Sharma’s allegedly provocative statements that hurt the Muslim community, answers to the following questions become relevant: what are the essential contents of free speech as a right in a civilised constitutional democracy and what are the reasonable limitations attached to it? What constitutes that narrow line that differentiates an act of free speech from hate speech and how does one identify this distinction?

The turning point

The fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression as under Article 19(1)(a) of the Indian Constitution is the very source from which every civil and political right flows. Indeed, freedom of speech is a right that cannot and must not be unreasonably curtailed no matter how uncomfortable the speech may be. However, a speech loses its right to be protected, the moment it turns hateful or incites violence.

By calling everything an act of Jihad by the Muslim community, the media only normalises islamophobia and peddles fake news.

This distinction between free speech and hate speech has been repeatedly iterated by not just Indian courts, but also in other jurisdictions. For instance, in the case of Shyam Balakrishnan versus State of Kerala (2014), the Kerala High Court was very clear that a merely unpalatable ideology with uncomfortable beliefs does not constitute an offence in a democratic nation.

The court said “Being a Maoist is no crime, though the political ideology of Maoists does not synchronise with our constitutional polity. It is a basic right to think in terms of human aspirations.”

Similarly, making the understanding of freedom of speech and expression abundantly clear, the Delhi High Court, in the case of Priya Parameswaran Pillai versus Union of India and Others (2015), stated:

“Criticism, by an individual, may not be palatable; even so, it cannot be muzzled. Many civil right activists believe that they have the right, as citizens, to bring to the notice of the State the incongruity in the developmental policies of the State. The State may not accept the views of the civil right activists, but that by itself, cannot be a good enough reason to do away with dissent.”

Hate Speech falls short of being free speech when it turns violative of the law against propagation of hate and/or incitement of violence. The reasoning that can be inferred for this reasonable restriction is that it vitiates the very purpose of free speech, which is the free and fearless operation of a human mind that constantly seeks answers and the truth. This can be explained by the harm principle proposed by political philosopher and an advocate for individual liberty – John Stuart Mill.

It is an undeniable fact that there is an accentuated and institutionalised effort towards the demonization of the minority Muslim community in India.

The harm principle states that any action, all actions of individuals must be permitted as long as they do not cause harm to any other individual. Clearly, hate speech propagates hatred towards individuals or social groups which may even incite violence and therefore, cause significant harm to others. In itself, hate speech violates the very essence of the social contract which guarantees rule of law and protection from chaos of the rule of the jungle.

Legislative objectives

In the case of Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan versus Union of India & Others (2013), the Supreme Court relied on Canadian jurisprudence from the cases of Saskatchewan (Human Rights Commission) versus Whatcott (2013) and Canada (Human Rights Commission) versus Taylor, (1990) to prescribe a three-step method to determine hate speech.

Firstly, the courts must apply the hate speech prohibition objectively. The question courts must ask is whether a reasonable person, aware of the context and circumstances, would view the expression as exposing the protected group to hatred.

Second, the legislative term “hatred” or “hatred or contempt” must be interpreted as being restricted to those extreme manifestations of the emotion described by the words “detestation” and “vilification”. This filters out expression which, while repugnant and offensive, does not incite the level of abhorrence, delegitimisation and rejection that risks causing discrimination or other harmful effects.

Third, tribunals must focus their analysis on the effect of the expression at issue, namely whether it is likely to expose the targeted person or group to hatred by others. The repugnancy of the ideas being expressed is not sufficient to justify restricting the expression, and whether or not the author of the expression intended to incite hatred or discriminatory treatment is irrelevant. The key is to determine the likely effect of the expression on its audience, keeping in mind legislative objectives to reduce or eliminate discrimination.

Hate Speech falls short of being free speech when it turns violative of the law against propagation of hate and/or incitement of violence.

Similarly, the Rabat Plan of Action, which is a framework formed by the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR), outlines a six-part threshold test to understand hate speech. The test takes into account : 1) The social and political context, 2) Status of the Speaker, 3) Intent to incite the audience against a targeted group,4) Content and form of the speech, 5) Extent of its dissemination and 6) Likelihood of harm, including imminence.

Obnoxious influence

It is an undeniable fact that there is an accentuated and institutionalised effort towards the demonization of the minority Muslim community in India. In fact, observers have repeatedly warned and drawn similarities between India’s treatment of the minority Muslim community, its media’s participation in spreading disinformation against the Muslim community, a consorted effort to vilify and demonise all Muslims, and Dharm Sansads calling for open killing of Muslims, as ominous signs of impending genocide.

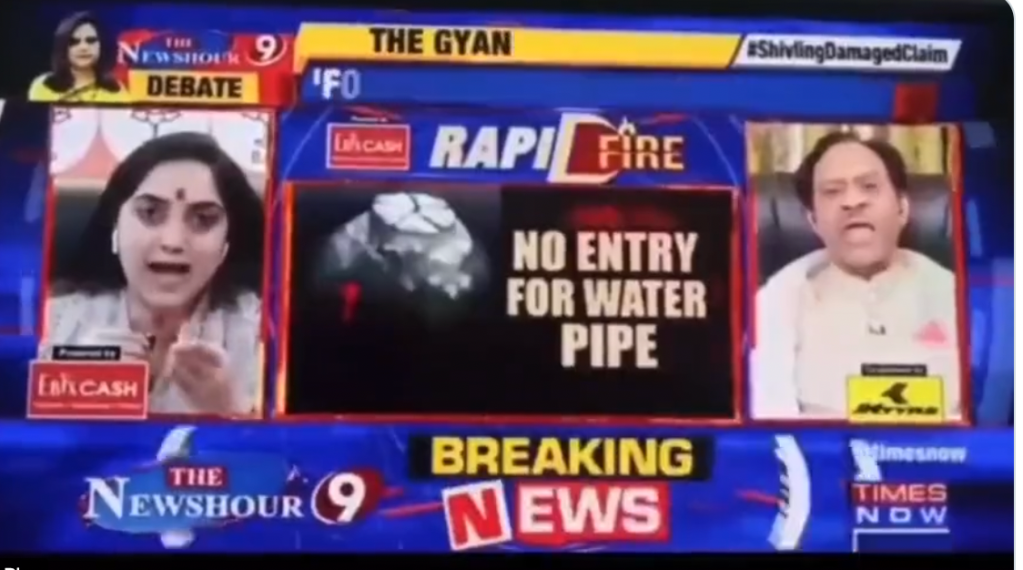

In normalising hate speech against minorities, the role of the media is palpable. By calling everything an act of Jihad by the Muslim community, the media only normalises islamophobia and peddles fake news. Indeed, the current situation of hate speech dystopia is everything that a healthy constitutional democracy must not be.

With the advent of social media, WhatsApp and several other sources of unverified information, hate speech is just a click away. Death threats, rape threats, morphed images, and fake auction of Muslim women have become normal online. Hate speech, when injected regularly over a period of time, has the ability to alter our minds, faiths, convictions and compel us to reject the rule of law and stability of a constitutional democracy and reasoned thought process and return to our animalistic instincts of chaos and murder.

(Ujjaini Chatterji is an Advocate based in Delhi)

Also Read:

Right to dissent without violence and hate speech part of freedom

After Supreme Court judgment, we must combat hate speech from social and political levels

Related

Commentaries