Why did Gauri Lankesh die? A review of Rollo Romig’s book on Gauri Lankesh

Eight years ago, at about 7.45 pm on September 5, 2017, senior journalist Gauri Lankesh, editor of Gauri Lankesh Patrike was shot dead at point blank range as she was entering her home in Bengaluru.

An outspoken critic of right-wing extremism, she minced no words in her writings or speeches. Gauri knew the risks of confronting majoritarian politics but refused to stay silent. She had received several death threats over the years. Her killing, which bore remarkable similarity to the murders of three other secular rationalist intellectuals* seemed to be a part of a pattern in the brutal elimination of dissenting voices.

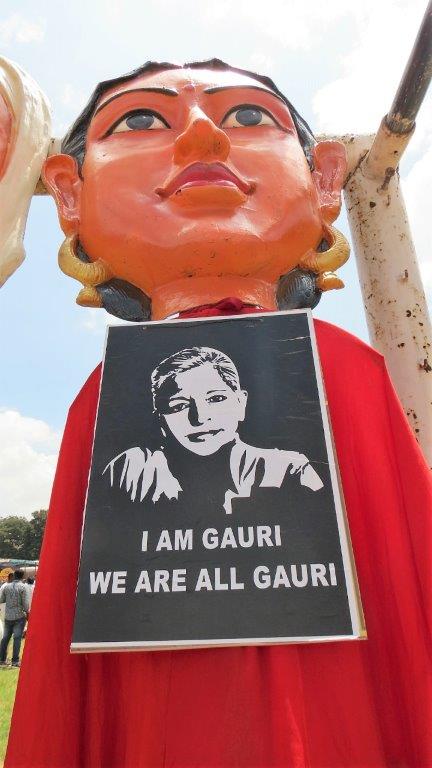

Photo by Laxmi Murthy from the first public meeting a couple of days after her killing on 5 September 2017.

The trial only began in 2022, nearly five years after her killing, and has been plagued by delays. Earlier this year, on January 8, 2025, a Bengaluru court granted bail to Sharad Bhausaheb Kalaskar, the last accused still in custody. This means that 17 out of the 18 individuals initially arrested in connection with the 2017 killing are now out on bail. One accused remains absconding and is believed to have fled the country.

On the eighth anniversary of her assassination, Gauri’s killers still walk free.

In her review of Rollo Romig’s book, I Am on the Hit List: Murder and Myth-making in South India, Laxmi Murthy** writes how the book uncovers the making of Gauri Lankesh, her fight against Hindu nationalism, and how the journalist’s murder exposes the cost of dissent in an increasingly intolerant India.

This review was first published in Himal Southasian and has been reprinted here with permission.

Why did they kill Gauri Lankesh?

Rollo Romig’s book uncovers the making of Gauri Lankesh, her fight against Hindu nationalism, and how the journalist’s murder exposes the cost of dissent in an increasingly intolerant India

In a land where the majority is quick to take offence, and “hurting religious sentiments” is a crime, any transgression can be deadly. The food we eat, the clothes we wear, the books we read, our language and, indeed, the words we speak, are subject to intense surveillance in India. The price to be paid for a perceived offence can range from abuse on social media, a court case that drags on for years, a physical attack or even death. Many of those deemed offensive are aware of the risks they take, yet they do not back down. Regardless, they speak up.

Rollo Romig’s eloquent telling of the story of the slain journalist Gauri Lankesh, one such fearless soul, is more than just a murder mystery, more than just an exposition of India’s politicised policing, its dysfunctional justice system, the vulnerability of these to power or money. In asking questions about why certain people murder, how they overcome moral qualms, and what gives them the ability to eliminate voices they dislike, Romig explores, with great finesse, the politics and philosophy of hate and intolerance. I Am on the Hit List: Murder and Myth-making in South India is also Romig’s paean to his adopted country by marriage, teetering somewhat dangerously between breathless admiration and cynical realism in how he views the grand mess that is India. But it is the empathy he musters and the access he secures to those who were close to Gauri that allows him to present an intimate and authentic picture of the activist-journalist in all her complexity. Following Gauri’s murder in Bengaluru on 5 September 2017, it has been easy and somewhat predictable to cast her as a saint, to etch her martyrdom into history. But Rollig, a journalist himself and faithful to the tiny details, shows her to have been all too human. He points out that Gauri, the irreverent iconoclast who defied convention, “spent the last thirty minutes of her life in the most ordinary Bangalore way: in traffic.” The lack of a parking space near her office in the crowded residential area of Basavanagudi, where she returned for a forgotten tiffin of biryani, made her wait in her car while Prasad, her office assistant, brought it down to her. Her parting words were poignant: “Goodbye, goodbye, goodbye.” She drove home only to be shot at point-blank range, and died on her own doorstep.

“What must have gone on in her mind?” wonders her close associate Shivasundar, who remembers in the book that Gauri was afraid of getting injections. “We feel very bad when we think about it.” The murder caused outrage across the country, and her funeral cortège saw thousands of people from all walks of life pour onto the streets, in grief and in protest. Placards saying “Naanu Gauri” – “I am Gauri” – were held up high as waves of people mourned in total identification with her.

What was it about this five-foot tall firebrand that threatened someone enough to have her murdered? At what point did online abuse tip over into real-world harm? Who had she angered, and why?

In tracking the murder investigation, Romig meticulously takes the reader through all the theories floating around: it was a bungled robbery, or the Naxalites (a theory supported by Gauri’s brother, Indrajit), or a property dispute, or maybe the Hindu Right. The last is the most plausible because Gauri was a vociferous critic of the Hindutva project, especially as it made inroads into Karnataka as part of what Romig terms India’s “rapid descent into autocracy.” Gauri Lankesh Patrike, the weekly tabloid that Gauri owned and edited, might have been tiny, but as Romig points out it was generally agreed that “its uncompromising, sometimes jeeringly inflammatory Kannada-language reports on intensely local issues might have provoked an outsize backlash.”

When Gauri was killed, Narendra Modi of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), a scion of the Hindu Right and arguably the most divisive prime minister the country has ever seen, had been in power for three years – time enough to herald the dangers that were now normal. From the time he assumed office in 2014, Gauri lambasted Modi every week in her column, “Busi Basiya” – which means “bluff master” in Kannada. Since her murder, Modi has been elected twice more – most recently in 2024, this time slightly less convincingly, but still with enough of a majority to continue his steady erosion of democratic institutions. Under Modi, the hegemonic project of Hindutva has not only flourished across the Hindi-speaking “cow belt” of northern India, where it has traditionally found fertile ground, it has also steadily penetrated the country’s south, hitherto more diverse in terms of language, culture and politics.

Gauri was blunt in her critique, roundly denouncing the Hinduism espoused by once-fringe Hindu extremist groups that were rapidly taking centre stage and whipping up hate on social media. The Special Investigation Team probing the murder found a video of one of Gauri’s speeches on the phone of one of those accused in the case. An investigation by Forbidden Stories, an international network of journalists, also found that the video had spread across the country in far-right circles, and had been disseminated by the official BJP Karnataka Facebook page.

The “offending” speech in the video was made in the city of Mangaluru in 2012, immediately after a Hindu radical group had attacked a homestay where a group of young people was celebrating a birthday. Around 40 goons claiming to belong to an outfit called Hindu Jagarana Vedike beat, stripped and molested the young women present for allegedly consuming alcohol and engaging in “indecent activities.” Gauri was scathing: “What kind of Hinduism is this? I reject it!” Twelve years later, in August 2024, the 39 accused in the “homestay case” were acquitted due to procedural lapses on the part of the police, which led to the rejection during the trial of video evidence and victims’ testimonies.

Romig traces Gauri’s journey from an unremarkable journalist with a mainstream English-language daily to a writer firmly embedded in Kannada journalism, determined to make a difference. Her metamorphosis into an activist in the early 2000s can be comprehended only by understanding the context in which this transformation took place. She threw herself into issues that were roiling Karnataka. Secularism and constitutional values were not mere precepts for Gauri, who was passionate about protecting the cultural diversity of the state against the onslaught of a monolithic Hinduism.

The shrine of a Sufi saint, Baba Budan, in the hills of Chikmagalur, equally revered by Hindus and Muslims, was representative of Karnataka’s syncretic culture. But it was being claimed as a solely Hindu place of worship. Court cases, popular movements and protests over the site’s fate peppered the 1990s, and in 2002 Gauri agreed to go on a fact-finding mission organised by the Baba Budangiri Harmony Forum. The impulsive decision, Romig writes, “re-routed” her life: “It was atop that mountain that she began her transition from ‘objective’ journalist to activist-journalist.” According to Girish Karnad, the famed Kannada playwright and another member of the fact-finding team, it was also where she “flowered”.

To answer the question of how Gauri – a fun-loving, hard-drinking party animal – became a vocal critic of Hindutva, Romig meets her sister, the filmmaker Kavitha Lankesh, as well as a wide circle of Gauri’s friends. Chidanand Rajghatta, her long-time friend and ex-husband, talks about how deeply Gauri had “waded into Lingayat politics despite being an atheist and having long been indifferent to her own Lingayat background.” She was attracted by the teachings of Basavanna, the founder of the Lingayat sect, who rejected rituals, temples, caste hierarchies, Brahmin hegemony and the authority of the Vedas. Ironically, the sect, founded in the 12th century, gradually solidified into a caste sub-group with its own rigid rules of endogamy – quite a departure from the beliefs of the radical Basavanna, who promoted inter-caste marriage in the face of vociferous opposition.

Gauri threw herself into Kannada journalism upon the death of her father, P Lankesh, in 2000, and tried to carry on his formidable legacy. Amid a life in academia, teaching English at Bangalore University, Lankesh began to be noticed as a prominent figure in the Navya literary movement in Kannada, rooted in modernism and ideologically socialist-leaning. In 1980, after his regular column in the Kannada daily Prajavani was cancelled – perhaps at the behest of politicians whom Lankesh lambasted at full throttle – he founded the first-ever Kannada weekly tabloid, which he named after himself: Lankesh Patrike. It was a blazing star, wildly popular and widely read. Serious literature, political gossip, humour and reportage all found their place within its pages. Karnad called him an “unmatched genius” as a journalist, and he is credited with bringing down the Karnataka state government in 1983 with his writings. “He created a new language, a new perception, a new way of looking at things,” Karnad said.

Lankesh’s was a hard act to follow. After his premature death at the age of 64, it seemed as if the only option was to shut the paper down. But, persuaded by the printer, staff who would be out of a job, and also her father’s close confidantes, Gauri reluctantly assumed editorship. It was hard to take her seriously at first, and no one really expected much.

But Gauri proved them wrong. At 38, she fast-tracked the development of her Kannada, which had been rudimentary at best. She clued herself up on Karnataka politics and literature, and, like many new converts, veered towards a form of language chauvinism dangerously close to Kannada nationalism, which was in the ascendant when Gauri took up the editorship of Lankesh Patrike. While she never occupied her father’s chair or his desk, she wholeheartedly adopted Lankesh’s signature style of aggressively putting the powers that be in their place.

Romig deftly traces Gauri’s activism alongside her work as editor. With the 100-year-old freedom fighter H S Doreswamy and others, as part of the Citizens’ Initiative for Peace, Gauri was involved with negotiating between the government and Naxalites who wanted to surrender their arms. While condemning the use of violence, she recognised the legitimacy of their struggles and wrote about the Naxalites with empathy, which led to her being labelled a Naxal sympathiser. There was a personal connection that perhaps moved her – a classmate of hers from journalism school, Saketh Rajan, under the nom-de-guerre “Prem”, was the leader of the Naxalites in Karnataka. His killing in 2005 by the police led to a series of retaliatory killings, and Naxal sympathisers and collaborators were being hunted down as well. Her brother, Indrajit Lankesh, as owner and publisher of Lankesh Patrike, wanted Gauri to stop writing about Naxalism. She refused.

From their schism was born Gauri Lankesh Patrike, a title she had registered possibly in anticipation of a split. It was an uphill struggle, and debt loomed large. Yet, professionally, she bloomed. Romig writes, “To Gauri, her principles and priorities had become clear. She abandoned the cautious pose of objectivity that defined the mainstream journalism of her early career. She wrote: ‘While activism gives our journalism a heart and a perspective, journalism gives our activism comprehensive understanding of and a sensitivity to context’.”

In the spirit of balanced reporting, Romig also presents the views of the “other” side, here comprising interviews with functionaries of the BJP who legitimise fringe Hindu extremist groups such as the one most likely linked to Gauri’s murder – the Sanatan Sanstha, with its roots in Goa. Whataboutery abounds, and questions are invariably raised about 24 Hindu activists supposedly killed by “terrorists”. Systematic digging reveals that most of these killings were over personal disputes and not politically motivated. Insinuations about Gauri’s lifestyle – drinking, living life on the edge, being “coarse” – stop just short of blaming her for her own death.

The “South India” in the book’s title is somewhat of an overreach, since Romig, in what he calls “detours”, tells a story from only three of India’s southern states: Karnataka, where Gauri lived, worked and died; Kerala, where he “digs into the mysteries” of ancient Kerala”; and Tamil Nadu, where he explores “the kitchens of modern Tamil Nadu.” Occupying 52 pages, these interludes, inserted into the narrative, seem somewhat contrived and unnecessary.

In discussing “myth-making” around martyrdom, Romig draws unconvincing parallels between the hagiographies of Gauri after her death and those of Thomas the Apostle – the Christian saint also called “Doubting Thomas”, who according to tradition is said to have died in 72 CE in what is now Chennai. Some Christians in Kerala believe that Thomas arrived in Kodungallur, on the Malabar Coast, in 52 CE, to spread the word of Christ. Romig’s quest to unravel the story of the saint takes him to ancient shrines in Kerala and Chennai, and also to archaeological sites in Kerala’s Pattanam, where excavations have unearthed evidence of ancient maritime links between the Roman Empire and the Malabar Coast. The excavations faced strong opposition from right-wing organisations that saw them as an attempt to legitimise the myth of Saint Thomas and his India connection. The archaeological project was shut down, pushing Thomas’s story out of the realm of verifiable history and back into the obscurity of myth. The connection to Gauri’s story is weak at best.

Another of Romig’s forays examines the tumultuous life of P Rajagopal, the “dosa king” who founded Saravana Bhavan, now a global restaurant chain. A so-called “low-caste” school dropout who broke into the business of vegetarian eateries, Rajagopal was sentenced to ten years in prison in 2004 for planning the 2001 murder of Santhakumar, the husband of a woman he was obsessed with and wanted to make his third wife, as advised by an astrologer. Rajagopal spent most of his time in subsequent years out on bail on “health grounds”, and was jailed again in 2019, a few weeks after which he died of a heart attack. He steadfastly denied any connection to the murder. “The thing that amazes me most about this murder is that those who did the actual killing were not professional hit men but simply Rajagopal’s restaurant employees,” Romig writes. “What could possibly have compelled them to murder for this man, and for his reasons? … It’s similar to the bafflement I feel about the men who actually killed Gauri (as opposed to the men who planned and ordered her killing.)”

It is for this inquiry into the human mind, into the puzzle of motivation and drive, that one can excuse the long detour into the life of the “dosa king”. What motivated Gauri’s killers? Was it religious belief, ideological conviction? Money? Or was it merely the following of orders? Was it militant Hinduism, machismo, lack of moral conscience, or a belief that they had divine approval for their deed? Jayant Athavale, the leader of the Sanatan Sanstha, was seen as a god by his followers, and his monograph Spiritual Practice of Protecting Seekers and Destroying Evildoers contains this oxymoron: “Violence towards evildoers is non-violence itself.”

Parashuram Waghmare, who pulled the trigger, apparently had no idea who Gauri was until he was assigned to kill her. “Conspiracies have powerful momentum,” Romig writes. “The more conspirators there are, perhaps, the more momentum the plot has, and the commitment of your fellow murderers, their apparent lack of doubt, makes the plot seem reasonable, sensible, inevitable.”

Understanding Gauri’s killing as part of a pattern makes the larger game plan more obvious. From 2013 onwards, numerous prominent activists and thinkers in India speaking out against religious dogmatism and superstition have been murdered in cold blood: the physician and rationalist Narendra Dabholkar, killed in Pune in 2013; the Communist activist Govind Pansare, killed in Kolhapur in February 2015; and the rationalist scholar M M Kalburgi, killed in Dharwad in August 2015. Investigations have since revealed that the Sanatan Sanstha was implicated in each of them.

A surgeon by the name of Virendra Tawade groomed what Romig calls “The Nameless Group” – a small, well-trained team of assassins, motorcycle mechanics, arms procurers and used-car salesmen – to carry out the assassinations. The book’s meticulous retracing of the group’s creation and piecing together of its methodology is done in the best whodunit style, drawing the reader in to speculate about the “why” rather than the how. The most prominent question is: Why were the killers not stopped before they targeted Gauri two years after their last hit?

In November 2018, the Special Investigation Team filed a 10,000-page chargesheet naming 18 persons involved in the murder of Gauri Lankesh. As of this writing, 17 of the accused are out on bail, and one is absconding.

It is a pleasant relief in Romig’s book to not have to read familiar Indian terms like “chappals”, “biryani”, “dosa” and “idli” in italics, and to see usage of “lakh”. I Am on the Hit List is replete with little vignettes from the haunts of Bengaluru’s intelligentsia. Romig meets the author and historian Ramachandra Guha in the legendary Koshy’s café, with its high ceilings, white-uniformed waiters and a corner table that the proprietor, Prem Koshy, still refers to as “Gauri’s table”. He chats with Gauri’s ex-husband, Rajghatta, in the archaic Bangalore Club, subjecting himself to scrutiny over his footwear in observance of its strict dress code. He frequents the bookstores on Church Street, “arranged with precisely the right degree of imprecision to maximise the book buyer’s sense of discovery.” Romig captures the essence of Bengaluru – the city in which Gauri worked and lived most of her life, and where she was buried in accordance with Lingayat custom. Her tombstone, in the Lingayat Rudrabhoomi burial ground at Chamarajpet, reads, “Look, the seed that’s sown here has sprouted all over the world.”

In an email to Rajghatta a year before she died, Gauri wrote, “The world is becoming insufferable to live in. I hope I can have a decent and safe and quick exit soon. Seriously. I have had enough of fighting against the fascist forces … but somewhere, deep inside me hope lives. After all, we kannadigas are products of Basavanna … we have a heritage which is rich in social harmony, social justice and economic equality. … despite my despair I am sure that we shall overcome our present challenges.” One can only hope.

*(i) Doctor and rationalist Narendra Dabholkar, shot by two motorbike borne men on August 20, 2013, in Pune; (ii) Author and politician Govind Pansare, shot by two motorbike borne on February 16, 2015 in Kolhapur; and (iii) Scholar, rationalist and teacher MM Kalaburgi was shot dead when he answered the door of his house to two motorbike-borne men on August 30, 2015.

**Laxmi Murthy heads the Hri Institute for Southasian Research and Exchange and is a Contributing Editor for Himal Southasian.

Related