Highlights

The first four months of 2025 have not boded well for the freedom of speech and expression in India. Censorship was rife, through direct and indirect attacks on free speech and press freedom.

The Free Speech Collective’s (FSC) Tracker reveals that in the first four months of the year alone, two journalists – Mukesh Chandrakar and Raghvendra Bajpai – were killed, four were attacked, six were arrested while there were at least five instances of threats and harassment.

‘Lawfare’ or the strategic use of laws to impede media freedom continued, with at least five cases lodged against journalists while two independent news media portals found their non-profit status revoked by Income Tax authorities, severely crippling their economic independence.

YouTube channels, including at least two news channels, were blocked.

The unrolling of government regulations detrimental to media freedom continued, with the Maharashtra government pushing its draconian Maharashtra Public Security Bill.

The precarious state of press freedom must also be seen in the context of the general deterioration of free speech in India, with vandalism and criminal complaints lodged by politically motivated sections of society that targeted academics, students, stand up comics and satirists, actors and film-makers.

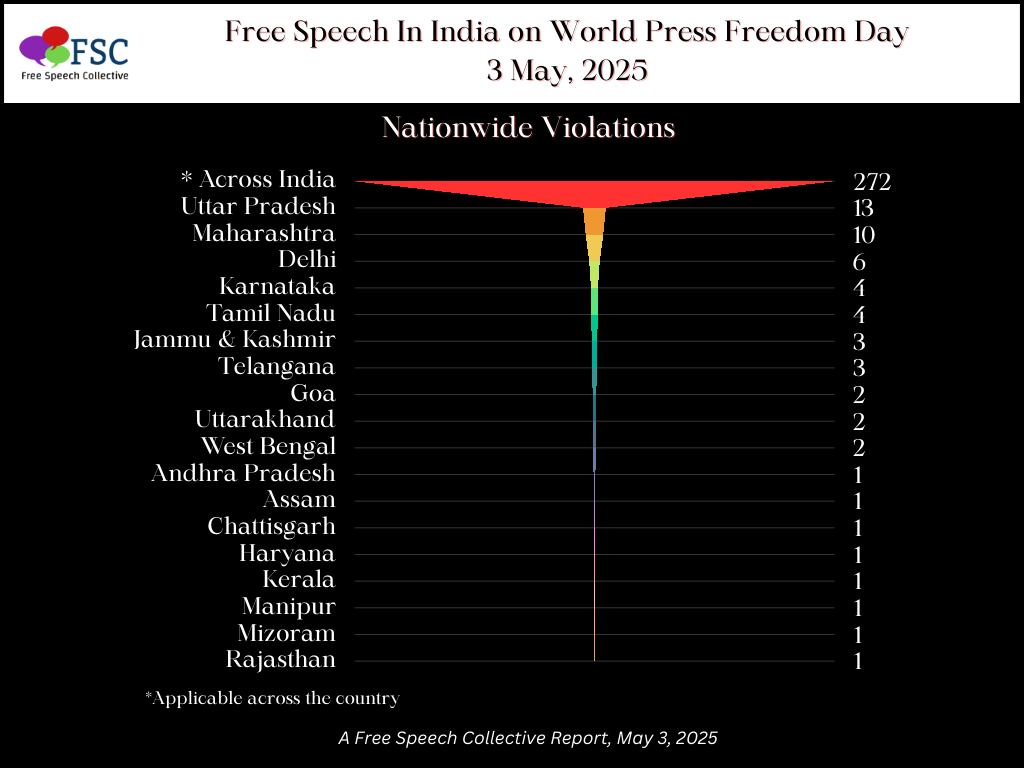

FSC tracked at least 329 instances of free speech violations (including those affecting news media, cited above) against citizens across all categories in the first four months of this year.

2025 started on an ominous note, with reports of the disappearance of Mukesh Chandrakar, a journalist who ran a popular YouTube channel ‘Bastar Junction’ from Bastar in Chhattisgarh. The foreboding turned to shock as journalists found his body three days later, crammed in a septic tank in the house of Suresh Chandrakar, a road contractor.

A post-mortem revealed that Mukesh Chandrakar was brutally beaten with multiple injuries inflicted by a very heavy object. The contractor, also related to him, was reportedly angry that Mukesh was part of a report on poor road conditions aired in NDTV on December 25,2024. Suresh Chandrakar was absconding, and it was only after a sustained protest by local journalists that the police and administration lodged an FIR and nabbed Suresh near Hyderabad.

Chandrakar was a lively and passionate chronicler of the people of Bastar, engaged in a daily struggle for existence in the midst of a more than 50-year-old conflict between armed insurgent groups and the security forces. The snuffing out of his life exemplifies the tenuous state of press freedom in India as journalists in smaller cities and towns continue to publish reports of the powerful nexus between corrupt local business and the political administration.

At this point, two journalists -Rupesh Kumar Singh of Jharkhand and Irfan Mehraj of Kashmir, arrested on July 17, 2022 and March 23, 2023 respectively, under the draconian Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), 1967, Mahesh Langa, senior journalist with The Hindu, arrested under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002, on Oct 9, 2024 and Tushar Kharat of Maharashtra, arrested under criminal defamation charges under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 on March 9, 2025 – continue to remain in custody in India.

Mehraj, a prominent journalist and researcher, was arrested on March 20, 2023 in a case related to terror funding while Rupesh Kumar Singh was arrested on charges of supporting Maoist activity on April 11, 2022. On March 10, 2025, Tushar Kharat, arrested in Mumbai on March 10, 2025, for airing allegedly defamatory content against rural development minister Jayakumar Gore in his Marathi YouTube channel ‘Lay Bhari’. All three have been denied bail by various courts.

In a shock and awe operation at 5 am on March 12, 2025, Pogadadanda Revathi, Managing Director of online news channel Pulse News, and Thanvi Yadav, a reporter with the channel, were arrested in Hyderabad for broadcasting allegedly abusive content against Chief Minister Revanth Reddy. A third person, who has an X account with the username, NippuKodi, was also detained for sharing the video. They were granted bail on March 17, 2025.

On March 25, 2025, Dilwar Hussain Mozumder, a reporter with the independent news outlet The CrossCurrent, was arrested in Guwahati for reporting on a protest about financial irregularities in the state-run Assam Co-operative Apex Bank. Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma is the Director of the bank and its Chairperson is the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) MLA Biswajit Phukan.

Following a vociferous protest by journalists’ organisations, he secured bail the next day but was promptly arrested in another case. He was finally released on bail on March 29, 2025.

All the journalists arrested this year are associated with independent YouTube media channels, an indicator of the shift of independent news publishing to digital and social media platforms. But the challenge to secure recognition and legitimacy remains.

The chief ministers of the states the journalists were arrested in – Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis and Telangana Chief Minister Revanth Reddy – denied any violation of press freedom and questioned the credentials of journalists working for independent and online news portals.

While Sarma took to ‘X’ to “clarify that Assam police has not arrested any journalist in recent times,” Fadnavis said the journalist was indulging in “extortion”. Reddy went a step further threatening “so-called journalists” in a speech on the floor of the state assembly and calling for them to be stripped and beaten in public.

The denial of recognition to independent news media continued in other forms. The Reporter’s Collective and Bengaluru-based Kannada website The File, both investigative news media portals registered as non-profits, found their non-profit status revoked by Income tax authorities, severely crippling their economic independence. The reasons given by the authorities is that their “journalism did not serve any public purpose”.

In a statement, The Reporter’s Collective said, “The order cancelling our non-profit status severely impairs our ability to do our work and worsens the conditions for independent, public-purposed journalism in the country.” Income Tax authorities maintained that The File was “a commercial venture” but its editors said that this was completely untrue and the website was an ad-free space.

In the aftermath of the tragic terror attack in Pahalgam, which left 26 civilians killed, pertinent questions about intelligence failures and security lapses posed by journalists and social media commentators were sought to be criminalised and blocked. Two YouTube channels – Knocking News and 4PM News – were abruptly blocked, the latter on grounds of national security.

Meanwhile, the unrolling of government regulations detrimental to media freedom continued, with the Maharashtra government pushing its draconian Maharashtra Public Security Bill, despite protests from journalists’ and civil society organisations. More than 12 organisations submitted objections to the bill, stated that its broad definitions for alleged unlawful activity were liable for misuse against legitimate journalistic work and criminalise journalists.

Free Speech violations across India

The precarious state of press freedom must also be seen in the context of the general deterioration of free speech in India, with vandalism and criminal complaints lodged by politically motivated sections of society that targeted academics, students, stand-up comics and satirists, actors and film-makers.

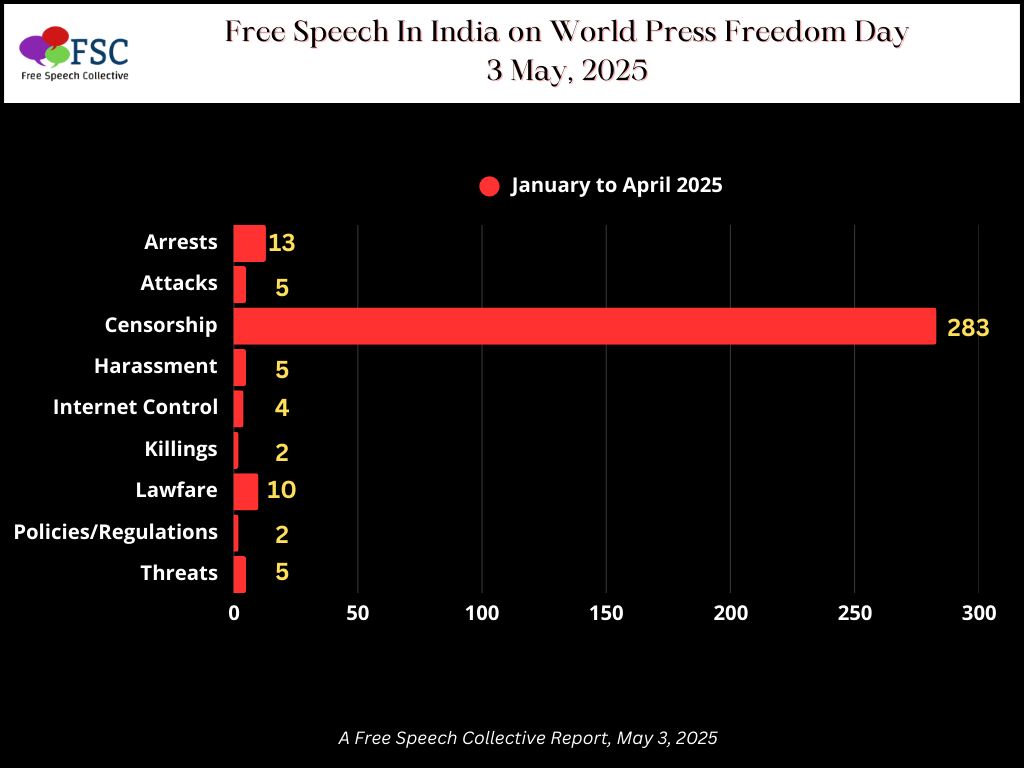

At least 329 instances of free speech violations were tracked against citizens across all categories by FSC in the first four months of this year, of which a whopping 283 instances were of censorship of both journalists and other citizens, in academia, the arts and in digital media.

The targets ranged from stand-up comics like Kunal Kamra, satirists and political commentators like Neha Singh Rathore, Madri Kakoti (aka Dr Medusa) and Shamita Yadav (aka the ranting gola) under draconian sections of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS).

Film censorship, pushed through by both the authorities as well as vigilante groups, continued. The enforced self-censorship of films like Empuraan and Phule, with crucial scenes and dialogues cut on the eve of, or after the film’s release, make a mockery of the certification awarded by the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC). While the multiple cuts suggested for Punjab 95, the cuts on foreign films screened for Indian audiences on OTT platforms and the flat denial of CBFC certification for award-winning films like Santosh are other alarming signals of excessive regulation.

The violence that broke out in Nagpur after the screening of the film Chhava or even the attack on Dalit journalist Sanjay Ambedkar while attempting to take audience reviews of the film Phule in Prayagraj for his YouTube channel Bheemraj Dastak.

In the face of this rampant censorship and clamping down on inconvenient truths that do not fit the official narrative, the pushback by civil rights organisations, journalists’ unions and associations has been encouraging. The constitutionally guaranteed right to freedom of speech and expression has occupied centre stage of public discourse, prompting much-needed responses from a range of citizens.

(For more information on the above cited instances as well as all instances of free speech violations, please visit the Free Speech Tracker.)