By Geeta Seshu

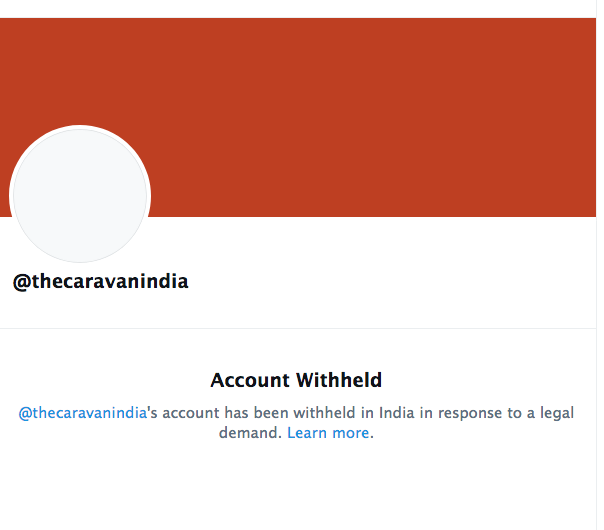

In the daily update on censorship in India, here comes the latest: Twitter blocks multiple accounts, including that of The Caravan magazine, actor Sushant Singh, writer Hansraj Meena and even the Kisan Ekta Morcha’s twitter handle.

Amongst the blocked accounts, pointed out journalist Mohd Zubair of Alt News, was the account of the Prasar Bharti CEO Shashi Shekhar.

Till date, there is no clarity from Twitter as to why these accounts are blocked or who has raised a legal demand to block them. This is all that Twitter tells us : In our continuing effort to make our services available to people everywhere, if we receive a valid and properly scoped request from an authorized entity, it may be necessary to withhold access to certain content in a particular country from time to time. Such withholdings will be limited to the specific jurisdiction that has issued the valid legal demand or where the content has been found to violate local law(s).

In the absence of any transparency, speculation is rife on the reasons for the block. While most of the handles are of dissenting voices and the magazine’s publishers and editors, Paresh Nath, Anant Nath and Vinod Jose, have been charged with sedition barely a couple of days ago. Caravan’s latest magazine issue has a cover story entitled ‘The Player – Akshay Kumar’s role as Hindutva’s poster boy, on the Hindi film actor’s fluctuating fortunes at the box office and his success at adopting themes that are in line with the government’s policies and progammes.

Kumar had interviewed Prime Minister Narendra Modi in April 2019 in what was billed as a ‘non-political interview’ a few months before the 2019 general elections.

Weirdly, according to the news agency ANI, around 250 accounts were blocked on an order from the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MEITY) because the accounts were using a hashtag ‘ModiPlanningFarmerGenocide’!

As it is, social media platforms, including Twitter, have been criticised for failing to act swiftly and decisively against hate pedlars and inflammatory speech on their platforms. Their regulatory mechanisms are opaque and uneven. They have almost no accountability to users, beyond general noises about adhering to lofty community standards. Desperate to increase their support bases and to leverage their reach to business products, these networks crumble easily when pressure comes from the top.

If Twitter India continues in this vein, perhaps it will also see the kind of mass migration to Signal or Telegram that Whatsapp experienced a few weeks ago, following its restrictive and unilateral privacy policy. Unnerved by the numbers, it was forced to issue clarifications and postpone bringing its new privacy policies into place. Likewise, with Twitter, Mastadon didn’t take off as much but public anger can well tip the scales in its favour (there are other alternatives to Twitter, of course, but this is just by way of example).

Media users need plural media platforms. That’s one way of ensuring that free speech is protected.