Republished from Indian Journalism Review, Jan 13, 2021.

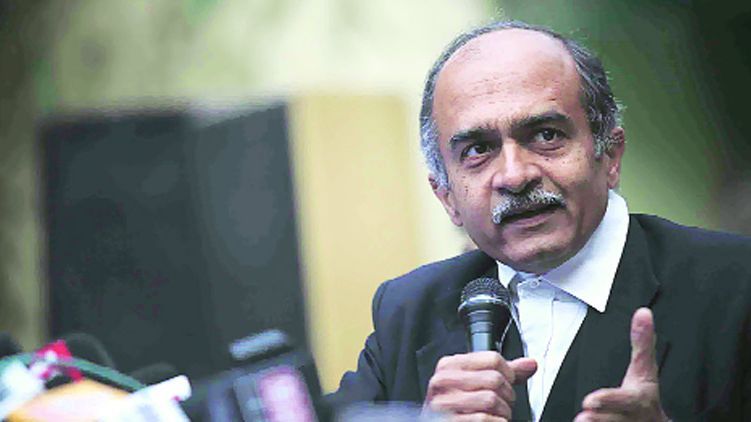

The constitutional validity of the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971, has been challenged in the Karnataka High Court by Krishna Prasad, former Editor-in-Chief of Outlook; N. Ram, former Editor-in-Chief of The Hindu and director of The Hindu Publishing Group; Arun Shourie, former Editor of The Indian Express and former Union minister; and Prashant Bhushan, senior advocate and noted civil rights activist.

The four petitioners—all victims of the Contempt of Court Act—want Section 2(c)(i) to be declared as being violative of Articles 19 and 14 of the Constitution of India; and want rules and guidelines to be framed to define the process that superior courts must employ while taking criminal contempt action.

The Contempt of Court Act, 1971, provides for civil and criminal contempt.

Civil contempt is defined under Section 2(b) as wilful disobedience to any judgment, order or direction of a court or wilful breach of an undertaking given to a court.

Section 2(c) deals with criminal contempt and attempts to punish publication of any material or commission of any act against courts. First, if such publication or act scandalises or lowers the authority of any court (sub –clause i); second, if it prejudices or interferes with any judicial proceeding (sub-clause ii) and third, if it interferes with or obstructs administration of justice (sub-clause iii).

The petitioners have challenged only Section 2(c) sub-clause (i), which criminalises any publication or act on the ground that it scandalises or lowers the authority of the court, on the following grounds:

1. It is violative of Aricle 19(1)(a): Section 2(c)(i) of the Contempt of Courts Act violates the right of free speech and express guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution.

2. It fails the test of overbreadth: Section 2(c)(i) has an extremely wide import and is incapable of being objective interpreted and even-handedly applied.

3. It criminalises speech in the absence of proximate and tangible harm: Section 2(c)(i) restricts speech on the basis of no more than its “tendency” to scandalise or lower the authority of the courts.

4. It has a constitutionally impermissible chilling effect: Section 2(c)(i) has a chilling effect on free speech and expression, and silences legitimate criticism and dissent to the detriment of the health of democracy.

5. It fails the test of proportionality: Not only does Section 2(c)(i) provide for conviction and imprisonment, it also impacts the fundamental right to reputation of the speaker or dissident.

6. It is has its origins in the colonial past: Section 2(c)(i) is anachronistic and untenable to exist alongside the constitutional guarantee of free expression, and the basic feature of a democratic and republican government.

7. It is incurably vague: Section 2(c)(i) lacks clear definition and uses vague terminology whose scope and limits are impossible to demarcate.

8. It is manifestly arbitrary: The vague wording of Section 2(c)(i) leaves it open to differing and inconsistent applications, and therefore violates the right to equal treatment under Article 14.

9. It has no clear guidelines: Unlike Section 2(c)(ii) and 2(c)(iii), there are no guidelines and rules for the application of Section 2(c)(i) so as to avoid the violation of the principles of natural justice and arbitrary exercise of power by individual judges.