by Geeta Seshu

High irony indeed, but a public meeting on a media blackout in Kashmir was literally blacked out by Delhi police.

The Campaign Against State Repression, a loose coalition of over 35 organisations representing students, workers and civil society, organised a public meeting on “Media Blackout and State Repression in Kashmir” on March 15, 2023, at the Gandhi Peace Foundation in Delhi. The venue was booked, payment for the hall made and invitations and posters for the meeting began circulating well in advance. Everything seemed to be in place for the meeting.

The speakers were also announced : Justice Hussain Masoodi, former judge of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) High Court , Prof. Nandita Narain, former President of the Delhi University Teachers Association (DUTA), M Y Tarigami, CPI(M) leader of J&K, Mir Shahid Salim, Chairman, United Peace Alliance, film-maker Sanjay Kak and journalist Anil Chamadiya.

The objective of the meeting was to focus on the ‘clampdown on the right to freedom of expression, by relentlessly attacking any mediahouse that criticizes the anti-people state policies carried out in Kashmir’.

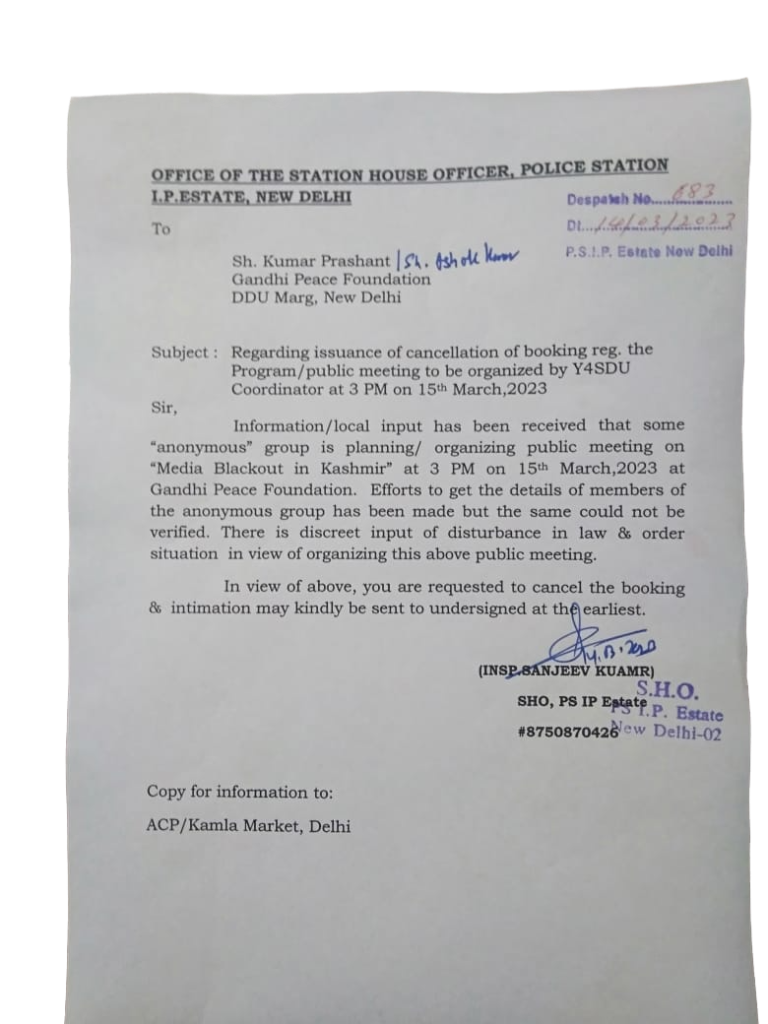

However, Delhi police decided that the meeting would be a threat to law and order and directed the Gandhi Peace Foundation to cancel the meeting. A letter from Inspector Sanjeev Kumar of IP Estate police station said that an ‘annonymous” group was organising the meeting and that there was ‘discreet input of disturbance of law and order situation” in organising the public meeting!

According to office staff at the Gandhi Peace Foundation, the police came to the venue the night before the meeting and wanted all information about the organisers and who had booked the hall. They told the staff that police permission had not been taken for the meeting and said that, henceforth, no meetings could be held at the venue without police permission. This was never the practice but the staff had to comply and cancel the meeting, they said.

It must be noted that the organisers were clearly identified and listed in the posters for the event, the name of the organisation and the person who made the booking was also available to them and yet their letter stated that police could not verify details of the anonymous group.The police didn’t give any details as to the “discreet inputs” on disturbance to law and order.

In any case, as a statement from the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) said, there is no need to take permission for an indoor meeting. The PUCL statement further said, “It is quite clear that the law and order problem is not the issue, real motive was to gag the freedom of speech on an important public issue involving rights of the people of Kashmir. Banning an indoor public meeting is totally arbitrary, malicious and unconstitutional. Even during the infamous ‘emergency (June 1975 to March 1977) indoor meeting opposing ‘the emergency’ were not banned. The present government and the police must remember what Gandhi ji said as far back as 1921, in a message he wrote in Young India, “ In a democracy people are not like sheep. In democracy we must jealously guard freedom of expression and thought and action.”

Can Police shirk their duty to maintain law and order?

The arbitrary police action begs the question: what is the role of the police in maintaining law and order in such situations? There are enough and more judgements from the Supreme Court that the job of the police is to maintain law and order, not force the cancellation of film screenings or theatre performances. From the Kamal Hasan starrer Vishwaroopam in 2013, to the Padmavat issue in 2018 or the attempts by West Bengal police to force theatres to cancel screenings of the Bengali satire Bhobishyoter Bhoot in 2019, the courts have upheld the right of film-makers to screen films.

In the Bhobishyoter Bhoot case, a bench of Justices D Y Chandrachud and Hemant Gupta observed that it would be ‘very, very insidious in a democracy’ if police directly wrote to theatres to cancel a screening. “It cannot be accepted that a film which is critical of political class is to hurt public sentiments. Under what authority and law, a police officer can write to theatre owners to pull down a particular film,” the judges said.

In the Padmavat case, the court was just as blunt. “Look, we have passed an order. 100 people cannot create some problem in a particular area and the state cannot say there is a law and order problem. Let us not come to a stage where exhibition of a movie of this nature after issuance of certificate is crippled. Let those who don’t like the movie not watch it” said then Chief Justice of India, Dipak Misra.

If the police tried arguing that a film screening is different from a public meeting, it could check out the Madras High Court judgement of 2017, where the fundamental right to hold a public meeting could not be denied on the mere apprehension of a law and order situation arising from the meeting. Then, Justice M S Ramesh categorically maintained that police could provide protection if they fear that anti-social elements could disrupt the meeting.

Controversially, the courts have also adopted a more benign approach towards meetings where there is apprehension of hate speeches and provocations to violence. The Sakal Hindu Samaj rallies in Mumbai and satellite cities were allowed on condition that no hate speech would be allowed and the police would videograph proceedings.

Kashmir Media and law and order

But what has the maintenance of law and order got to do with an academic discussion on Kashmir’s media ? As it is, the media in Kashmir is at its worst and lowest phase ever. Three Journalists and editors from Kashmir are currently in jail – Aasif Sultan since August 2018, Sajad Gul since January 2022 and Fahad Shah since February 2022. Charged under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) and Public Safety Act (PSA), their chance of securing freedom in the near future is remote.

Other journalists in Kashmir have faced intimidation, show cause notices, charged under UAPA, their houses, raided, taken off flights and denied even the chance of travelling to collect a Pulitzer Prize, as in the case of Sana Irshad Mattoo. Reportage is woeful and, as the redoubtable Kashmir Times editor Anuradha Bhasin said in this interview, there is intense surveillance and monitoring of every utterance of journalists. Most prefer silence. A new media policy in Kashmir dispenses advertising revenue and rewards the safe and uncritical. Important stories – whether of the environment, global warming, climate change, gender, child rights and civil liberties – are all but forgotten.

Any attempt to set the narrative right, especially in international fora, only faces outrage and rejection, as is evident by the reaction of India’s Minister of State for Information and Broadcasting Anurag Thakur to Bhasin’s edit piece in the New York Times. The minister actually said the courageous journalist was ‘spreading lies’ about India and that the opinion piece was mischievous and fictitious! Bhasin, who outlined the manner in which a new breed of young journalists had ‘brought a fresh eye to Kashmir’s problems” and public interest reporting that had all but “disappeared under Mr Modi”, had warned that the rest of India might end up looking a lot like Kashmir. Bhasin has said that she stood by her report.

Kashmir’s media has struggled with killings, arrests and immense pressure from all sides for years now. But, as the Free Speech Collective report said in September 2019 after the unprecedented communication blockade in the Kashmir Valley following the abrogation of Art 370: “The continuing shutdown of communication in the Kashmir valley has resulted in the throttling of independent media. As journalists continue to face severe restrictions in all the processes of news-gathering, verification and dissemination, the free flow of information has been blocked, leaving in its wake a troubled silence that bodes ill for freedom of expression and media freedom.”

These measures have sounded the death knell for the media in Kashmir.

The throttling of democracy

In this context, the cancellation of a meeting in Delhi on the media blackout in Kashmir on the orders of a local police station, only underscores the precarious condition of free speech and free debate and discussion. Film-maker Sanjay Kak, who was slated to speak, said, ” There cannot be a more stark comment on the media situation in Kashmir than the fact that a public meeting on the “Media blackout and State Repression in Kashmir” was itself the victim of gagging.

Kak observed that journalistic practice is quite unviable and local newspapers read like nothing more than rewritten press notes given out by the various arms of the State. He added, “It is out of such authoritarian steps that the abhorrent silence around the situation in Kashmir has been constructed. It’s important for people to take note that this silencing does not – and will not – stop at discussions of Kashmir alone: it has already fallen on various expressions of democratic rights in India. And this silence is not simply a matter of choking self-expression. It is fast becoming the throttling of democracy itself.”

Senior journalist Anil Chamadia, another speaker at the public meeting, was worried about the attack on the democratic sensibility of society. As he put it, there were three steps for destroying any democratic set up : “First is to capture free spaces by so called means of democratic processes. Second is to destroy those institutions that carry the legacy of democracy. But the third step is the most challenging which is to demolish society’s democratic sensibility.”

The attacks against any democratic discourse, he felt, were an attempt to destroy this democratic sensibility. “If such as a small and peaceful gathering in a towering Gandhian institution that believes in democracy and peaceful coexistence, is so threatening for the ruling forces, it means that we are standing on the threshold between democracy and authoritarianism,” he warned.

Were the local police jittery? Did they overreact? Will this incident set an unholy precedent, whereby all public meetings will require prior permission from the local police?

Time will tell where we are headed, but one thing is clear: as the Indian government tries to maintain its grip over the narrative of normalcy in the face of irrefutable evidence of alienation and insecurity, the clampdown over a public meeting on Kashmir’s media in the national capital only lays bare the bluster and fear at the heart of authority.

2 thoughts on “Delhi police cancels public meeting, still afraid of the “K” word!”