On May 1, 2019, Suhail Naqshbandi decided to call it quits from Greater Kashmir after four years of turning in a cartoon daily.

by Geeta Seshu

As Pulwama and other constituencies in Jammu and Kashmir go into the final phase of polling for the parliamentary elections on May 6, 2019, one of the Valley’s major English dailies is minus its brilliant cartoonist.

“It’s really, really tough. The self-censorship we impose on ourselves. I have to keep thinking of ways to draw cartoons that will not offend anyone. And I do this on a daily basis. It takes a toll on your nerves,” Kashmiri editorial cartoonist Suhail H. Naqshbandi told Free Speech Collective in an interview.

Five days ago, Suhail H. Naqshbandi had had enough. On his Facebook page, he wrote a moving post to announce that he had called it quits as an editorial cartoonist with Srinagar-based Greater Kashmir newspaper. But the decision to stop turning in a cartoon a day, which he had been diligently doing since 2016, was wrested from him not by any major confrontation or difference of opinion with his editors. Instead, it happened in the most debilitating manner, day by day.

“The censorship has been there for a long time. It wasn’t pronounced as much but it intensified recently, over the last couple of months,” he said. His Facebook message refers to the increasing censorship after February 2019 when he says the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting asked the Jammu and Kashmir administration to identify ‘resistance art’ in Kashmir.

In his post, he said:

The establishment’s pressure tactics were always there and the newspaper stood up against it most of the times and let me have the freedom of creating the cartoons. But of late, the chinks started forming in that defense and the pressure trickled down to everyone including me.

The levels of censorship became stringent especially after February 2019 when the Information & Broadcasting Ministry asked the J&K administration to identify what they termed as “resistance art” coming out from Kashmir. Basically any artistic or literary voice that protests against the oppression. I spoke against it one of the news reports of New Indian Express, which sought my quotes on it. Who knows whose wick I got with it.

In the wake of the suicide bomb attack on a CRPF convoy in Pulwama, which killed more than 40 CRPF paramilitary troopers on February 14, 2019, tensions were high, given the intense war-mongering and military actions that followed.

While truth was a major casualty in the post-Pulwama attack, dissent – even if satirical – became another. For Naqshbandi, the continued scrutiny of his work meant that cartoons stopped being published on a regular basis.

“I would ask why my cartoons were not being used and would get an indirect message that I should move away from political cartoons. Do environmental or social issues, I was told. I was not able to make cartoons against political personalities, against the regime. I can do satirical work but the options began to narrow down,” he says.

Naqshbandi, who had begun working in Greater Kashmir in 1998, began a daily cartoon called ‘Inside Out’. He left four years later but returned in 2016. Initially, the editors were supportive and the situation was not that bad, he said. So the decision to quit was not a spur of the moment one, he clarifies. It was a wrench to have to leave the cartoon space he had created and nurtured.

What made matters worse was the stoppage of government advertisements to newspapers in Kashmir, which had begun to cripple revenue considerably. “It translated into delayed salaries and then salaries were slashed by nearly 50 percent. This, coupled with the censorship, just became untenable. How much more could I devalue my work?” he asks.

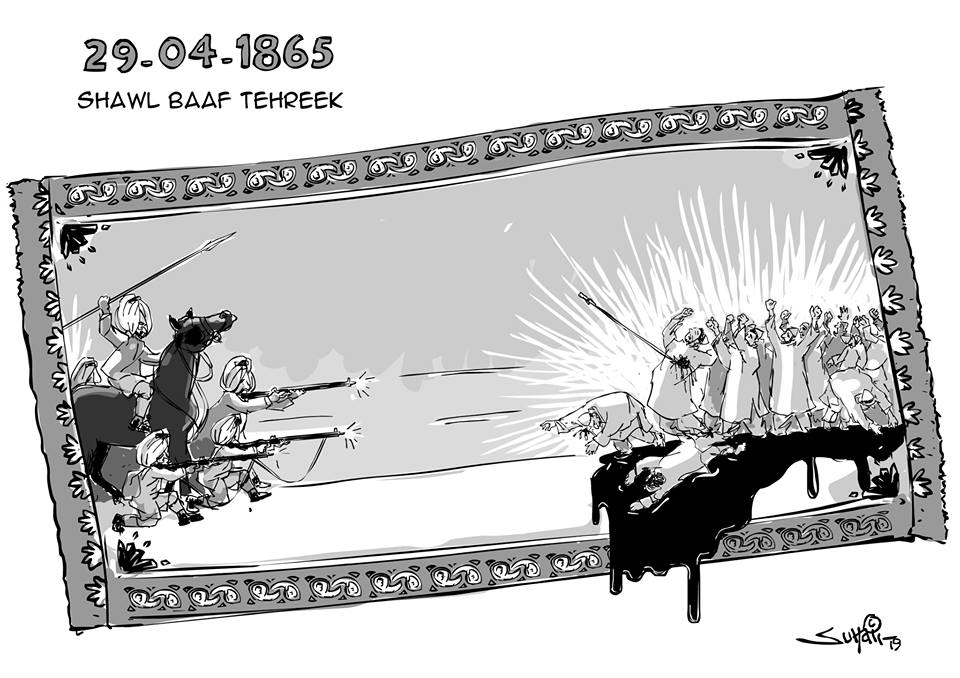

The final straw came when he submitted a cartoon about a protest by shawl weavers in 1865. The then dogra rulers had imposed a crippling tax on the shawl weavers and scores of them marched in protest in Srinagar on April 29, 1865. The Dogra army beat up the protestors and 28 weavers died as a result.

The cartoon, which used the motif of a shawl and the illustration of the killing within its borders to depict the historic incident, was not published. “This was ridiculous. It wasn’t even related to the present government,” he said.

Self-censorship : an unspoken reality

While the grim reality of a state in conflict forces its way though the shroud of censorship, the other side of the story is the ever-present self-censorship that most journalists, cartoonists and writers in Kashmir are familiar with. Naqshbandi was no exception. As he said, “I had started self-censoring a while ago. I was never told not to do this or that. But if I made a cartoon about the Home Minister for instance and it wasn’t published, I would get the message.”

He remembers the fate of another cartoonist who had a very direct and sharp style of cartooning, but was forced to leave almost every publication he worked for, until he was almost hounded out of the profession. He finally managed to find a job with a television channel outside Kashmir and has stopped working on anything to do with Kashmir.

Naqshbandi said in his Facebook post that he would take a break and ‘will be right back’. Sure enough, he has now begun posting his cartoons on his Facebook page, which he has tentatively titled ‘Come What May’. Here are two cartoons for World Press Freedom Day:

But what of the cartoons that were made but didn’t get published? Will the censor’s lie, as Rushdie feared, actually succeed in replacing the artist’s truth?

1 thought on “An Artist’s Bitter Truth”