The CBFC stamp of film censorship: Infantilising the public

The CBFC stamp of film censorship: Infantilising the public

Despite a firmly established judicial convention of trusting the “wisdom of the street”, administrative processes are turning towards infantilisation, says Sukumar Murlidharan, discussing the manner in which the CBFC has pandered to politics and the mob in ‘Janaki versus State of Kerala’.

Image Credit: IMDB

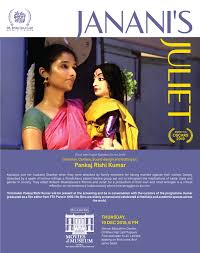

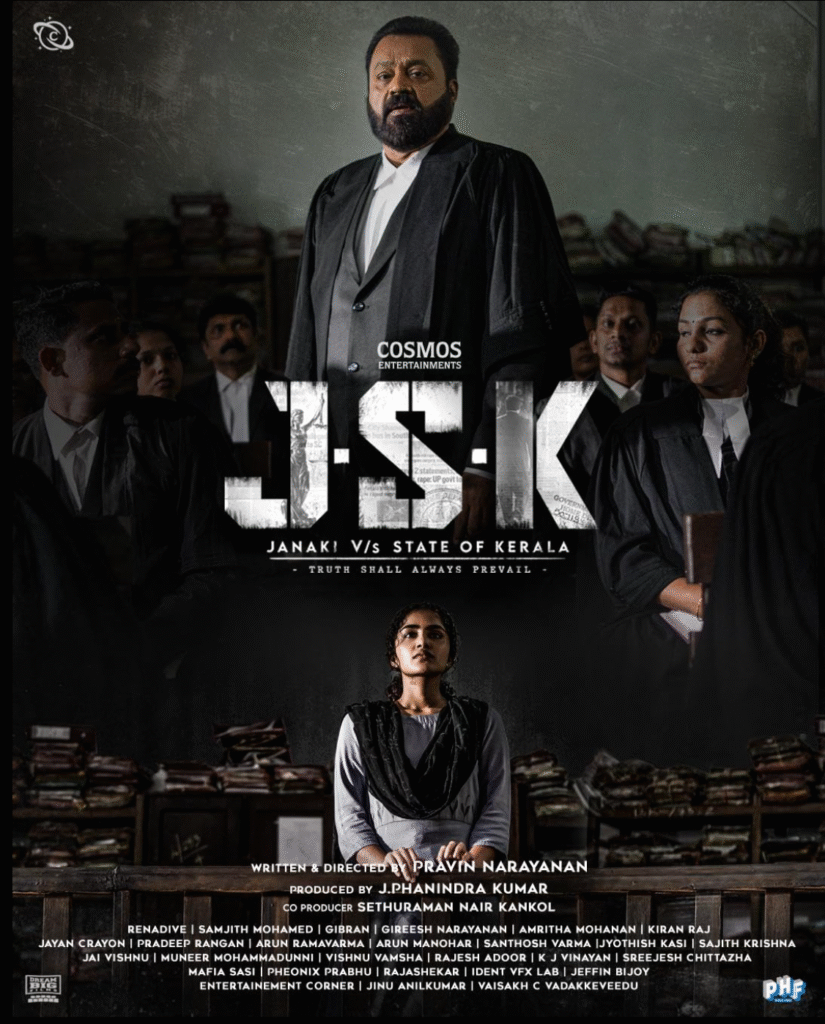

It was a court-room drama etched in celluloid, soon transformed into real-life farce. Advance publicity for Janaki versus State of Kerala suggested a plot involving a female victim and male saviour: a well-worn template for Kerala’s fading superstar Suresh Gopi to try and regain some of his aura. In the event, Gopi, who also happens to be a Union Minister and the BJP’s only MP from Kerala, was reduced to mute spectatorship as a perverse form of cultural policing took over.

J.S.K., as the film is titled in publicity posters, was approved for public release by the regional office of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) in Thiruvananthapuram. It was granted the U/A category, indicating no audience restrictions, though with parental guidance for children under 12. This necessary preliminary was completed well in time for the film’s planned release on June 17.

Rather than grant final approval, the CBFC central office referred the matter to a review committee, for reasons yet unspecified. The review in turn, demanded a change in name of the film’s main protagonist, Janaki, after whom the film is titled. A character bearing a name of divine provenance, it ruled, could not be portrayed as an assault victim.

Petitioned for a resolution, the Kerala High Court seemed to alternate between incomprehension and exasperation. No fewer than three hearings were held, after which the judges undertook to view the movie prior to final determination. This advances a new trend where the judiciary determines not merely matters of law and fact, but also cinematic aesthetics.

The mature audience

In ruling on freedom of expression matters, Indian jurisprudence has at various times invoked the imagery of a strong-minded and mature audience. This is a tradition that goes a long way back and embraces a range of contexts. In a case involving charges of sedition and the forfeiture of assets in 1946, a British judge, one of three members of a Nagpur High Court bench, held the case against a newspaper publisher justified. Justice Vivian Bose was joined by another Indian judge, in holding the opposite.

In the judgment authored by Justices Bose and Puranik, both intent and anticipated outcome mattered. Was there a seditious intent behind the material published in the newspaper? The answer was no: in a context of approaching elections, it was merely an appeal to use every available opportunity to oust the colonial Raj and choose a popular government.

Secondly, did the published material embody a credible threat of public disorder? Here, the judges held that the likely outcome of words spoken and written, was to be assessed against the benchmark of a “reasonable individual”. In words that have been reiterated many times since then and in various contexts, the judges put the matter as follows: “we must use the standards of reasonable, strong-minded, firm and courageous men, and not those of weak and vacillating minds, nor of those who scent danger in every hostile point of view”.

This formulation has since come to be applied in matters involving political speech as well as creative expression. In 1988, in the case of Ramesh versus Union of India, involving a TV serial Tamas, based on a novel of the same name by Bhisham Sahni, the Supreme Court upheld the standard of the “ordinary reasonable man”, to assess when creative expression strayed beyond admissible limits.

In S. Rangarajan versus P. Jagjivan Ram, the Supreme Court in 1989 declined to intervene in the public exhibition of a film that was sharply critical of the national policy on reservations in education and public employment for socially disadvantaged castes. The rationale was the same: the “standard to be applied for … judging the film should be that of an ordinary man of common sense and prudence and not that of an out-of-the-ordinary or hypersensitive man”.

In matters of political speech, this rationale was applied in the case of Javed Ahmed Hajam versus State of Maharashtra as recently as last year. It was a matter involving a college teacher of Kashmiri origin working in Maharashtra, who expressed his vigorous dissent on social media at the abrogation, in August 2019, of the constitutionally granted semi-autonomous status of his home state. Later the same month, he posted a “Happy Independence Day” message on the day Pakistan celebrated its freedom.

The Bombay High Court declined to grant relief from criminal prosecution in the matter. The Supreme Court ordered his discharge using the familiar rationale that the relevant test is of the “general impact of the utterances on reasonable people who are significant in numbers”.

Judicial vagaries in determining “intent” of speech

This case was one among many cited by the counsel for the BJP president J.P. Nadda and the party’s IT cell head Amit Malaviya, when they petitioned for discharge in a hate speech case filed by the Karnataka Police soon afterwards. The context was the general election to the Lok Sabha, with roughly half the constituencies in Karnataka scheduled to vote on May 7. On May 5, a post appeared across the BJP’s social media handles, stating that “If (the) Congress Party Comes to Power it will snatch Wealth of all Non-Muslims and distribute to Muslims, their Favourite Community (sic)”. This message was accompanied by graphic animations and video footage of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, digitally manipulated to make it seem that he was offering the Muslims of India the “first claim” on all resources.

In ordering the discharge of the two party functionaries, the Karnataka High Court ignored the other dimension of the 1946 ruling by Justices Bose and Puranik: on the intent of a certain speech act. Further, it was a ruling delivered with extreme alacrity, a mere seven months since the petition was filed, unusual for the Indian judicial system.

The other side of free speech jurisprudence is that for all the occasions that the “strong-minded audience” rationale has been invoked, it has been ignored in perhaps a greater number. The Bhima-Koregaon 16 and the Delhi riots accused are sufficient testimony of inconvenient speech acts being punished with prolonged imprisonment with no charge or prospect of trial.

Infantilising the public…with CFBC’s help

Despite a firmly established judicial convention of trusting the “wisdom of the street”, administrative processes are turning towards infantilisation, towards discounting the maturity of the public. And the CBFC has been active in alternately pandering to politics and the mob. In recent months, it has demanded alterations that threaten to fundamentally undermine the narrative structure of films such as Phule, on the life and times of the great Marathi anti-caste reformer, and Punjab 95, on a human rights defender’s disappearance as he was investigating a sinister police policy of disappearances.

In 2016, a newly constituted CBFC threatened to indefinitely hold up the release of Udta Punjab, a film on the growing contagion of drug addiction in Punjab. Elections to the state were due within a year, and the film was read as an attempt to influence its outcome by discrediting the party that held power. Dark hints were dropped about a partisan motive and a possible financial linkage with a political party. With the powerful Mumbai film industry rallying to the cause, this matter went swiftly through a judicial hearing, where the preposterous demands placed on the film maker were roughly dealt with.

The film Padmavati was a high budget production from the Mumbai film industry, built upon a medieval fantasy of love between a Muslim general and the consort of a Rajput king he went to war with. It is widely believed that the character of the woman was an invention of the Awadhi sufi poet Malik Muhammad Jayasi, as an allegory for unattainable beauty.

When the politically voluble Rajput community, particularly in the state of Rajasthan, threatened to burn down every movie hall that exhibited the film, the CBFC proposed a change in title to Padmavat, which reflected the title of the epic poem it was based on. That did not yet pacify the agitators who soon filed criminal cases against the film’s producer, director and actors. After the High Court refused relief, the principals had to approach the Supreme Court, which ruled in their favour.

The film Sexy Durga drew fire for conjoining a salacious epithet to a name of divine provenance. It was forced to alter its title to S Durga before being cleared for commercial release. By then it had won a string of international awards under the original title. And then, despite being chosen for the International Film Festival of India after a rigorous peer review by film professionals, the directorate of the event declined to allow its screening.

This level of censorial hyper-activity suggests not institutional health, but its opposite of corruption and imminent collapse. Much wisdom was assigned to the “street” in Indian jurisprudence. Today, the gatekeepers of creative expression seem to preempt the worst that the street can offer, indeed, to predetermine choices for them. Crushed between political intolerance and institutional corruption, the prospects for free speech have never before been so bleak.

(Sukumar Muralidharan is an independent writer and researcher based in the Delhi region. He was earlier a print media journalist, journalism trainer and instructor).

Related