The Second Silencing of Jaswant Singh Khalra

Why is the truth about human rights violations in Punjab being suppressed yet again asks Laxmi Murthy.

September 6, 2025 will mark 30 years since the abduction of Jaswant Singh Khalra, renowned human rights activist who meticulously documented and exposed extra-judicial killings, police “encounters,” and illegal cremations during the Sikh insurgency in Punjab between 1984-95. Khalra, a bank officer in Amritsar became politicized after seeing a pattern in abductions and killing of local youth by the Punjab police in fake “encounters,” starting from his village in Tarn Taran district of Punjab.

Image Credit: The Hindu

As he methodically investigated disappearances and illegal secret cremations by following the paper trail of purchase of firewood for various crematoria, he built evidence, kept impeccable records and held the authorities accountable. When uncomfortable questions were asked, and international pressure was applied on the Government of India, he was threatened, intimidated and finally silenced. He was abducted by the police in front of his Amritsar home while he was washing his car, tortured in police custody, and killed about two months later. His body, dumped into the Harike river, as testified by witnesses, was never found.

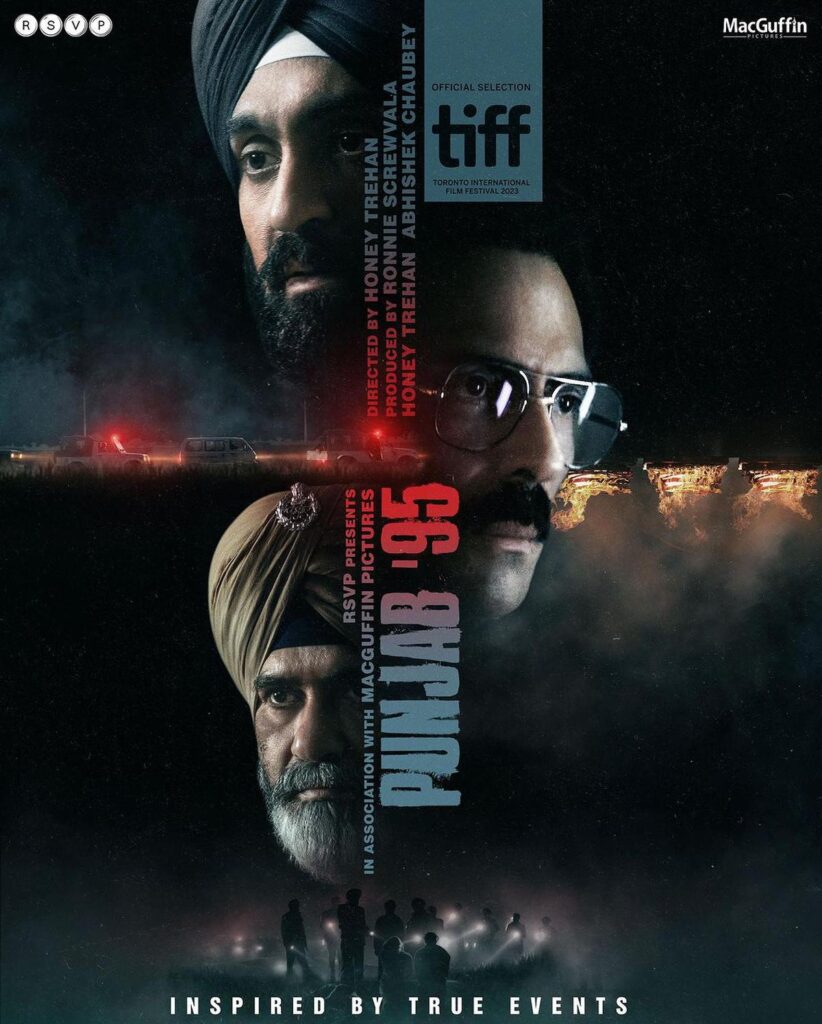

Khalra’s story, and that of enforced disappearances – estimated to have been about 25,000 – has been powerfully told in Punjab 95, a 2.29 hour film produced by Ronnie Screwvala’s RSVP films and directed by Honey Trehan. In 2020 during a period of Covid-induced quarantine, Trehan read Bangalore-based writer Amandeep Sandhu’s Panjab: Journeys Through Fault Lines which had a chapter on enforced disappearances. With a producer on board, and having obtained the rights from the Khalra family, Trehan approached Diljit Dosanjh who unhesitatingly signed up . Playing a character as revered as Jaswant Singh Khalra was a huge privilege. “Waheguru,” he said, and reverentially bent his forehead to the bulging file of research, relates Trehan. Dosanjh also waived his fees, as he was passionate about telling the heart-breaking story of this period in Punjab’s blood-soaked history.

Even though Khalra is respected almost like a saint, Punjab ‘95 is not quite a biopic. The crime thriller unfolds in dramatic ways, telling truths that must be told. There is also a subtle cross-over into the documentary genre – Diljit Dosanjh uses the original camera that belonged to Jaswant Singh Khalra to document evidence of police dumping bodies and overflowing crematoria. In the demonstrations and court scenes featuring families of the disappeared, they carry framed photographs of people who had actually disappeared, lending the film even more authenticity.

Interestingly, Dosanjh, 41, and Trehan, 46 were children during the insurgency and the excesses around it and felt deeply that this story must be told for a wider audience.

But the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) thinks otherwise. Submitted for certification in 2022, the film is yet to be released. Dealing with the CBFC, more widely known as the ‘Censor Board’ is a negotiation, rather than a one-time application process. This back and forth has been apparent to some degree. For example, the filmmakers agreed to change the original title Ghallughara (a term used to describe massacres of Sikhs since the 18th century) and 21 other cuts, after which it was certified ‘A’ in July 2023. They also reportedly agreed to defer the release until after the 2024 general elections, and even pull out of the Toronto International Film festival (TIFF). Variety magazine reported that any mention of the film had been removed from the TIFF website. These accommodations, hoped the filmmakers, would facilitate the film’s release.

In fact, on January 17, 2025, Diljit Dosanjh’s Instagram handle posted a seeming positive development “ਪੰਜਾਬ ’95 releases in Cinemas Internationally only on 7th February. P.S. Full Movie, No Cuts.” The announcement was premature, since the film was again mired in the CBFC quagmire. In May, the film was screened for a select audience on the side lines of the Cannes Film Festival.

But the censorship continues. General audiences the world over are still waiting to see Punjab ‘95. What’s the hitch? The filmmakers have not agreed to all the 127 cuts demanded, including the dropping of crucial words intrinsic to the film. Trehan says, “They want us to drop Punjab in conjunction with the police, to drop the name Jaswant Singh Khalra, to change the name of Tarn Taran, Amritsar and other places, the number of human rights violations that Khalra was researching, remove or reduce the scenes of Khalra’s torture and killing, remove national flags, drop mention of Canada, among other demands.” There is also a demand to drop ‘Inspired by True Events.’ “What will be left of the film, I wonder!” Trehan quips.

Filmmakers have to arrive at a balance between staying true to their original creation and wanting it to be widely watched. A ‘U’ or universal certificate means wider distribution, and some filmmakers might agree to delete some scenes of violence or sex deemed unfit for children. However, the process has become increasingly arbitrary, opaque and lacking in flexibility and tolerance for diverse perspectives, with the sword of “hurting sentiments” constantly dangling over filmmakers’ heads.

Describing the run ins with the CBFC that films like Pedro (Kannada), Aadhar (Hindi), Nasir (Malayalam) and many others, film critic Anna MM Vetticad writes, “…self-censorship and extra-judicial pressure to conform to unwritten restrictions is now routine across India, as writers, directors, producers and streaming platforms fall into line. The few who resist face attacks by virtual mobs and censor cuts or indefinite delays. A formerly swift appeals procedure has been dismantled, and judicial recourse is an uncertain process.”

It is not that Punjab ‘95 reveals new truths. State excesses during the insurgency in Punjab have been well-documented by human rights activists and academics. One that stands out is Reduced to Ashes: The Insurgency and Human Rights in Punjab (2003) by Ram Narayan Kumar is a meticulously researched inquiry into targeted political killings, enforced disappearances, torture, arbitrary detentions, and illegal cremations that characterised anti-insurgency operations in Punjab under KPS Gill, the then Director General of Police.

However, the power of good cinema is that creates wider ripples, and dare one say, waves. The reasons for the clampdown might be somewhat puzzling at first, since the film shows the Congress, in power at both the centre and the state, in a negative light. But what resonates with the current times is the sheer impunity for crimes committed by the establishment; the failure of the judiciary to protect human rights, and the undue priority placed on image building and white washing the narrative. Punjab ‘95 does however show a glimmer hope with the media asking questions and demanding answers – a rarity in today’s scenario of a compliant and complicit mainstream media. The ultra-sensitivity to what is perceived as international “interference” is also reflected in the nature of the cuts demanded. That human rights activists can forge solidarity at a global level is anathema to authoritarian regimes.

Denying and silencing the truth can never achieve peace, because without justice there can be no peace. “Challenge the darkness”, a tagline of Punjab ‘95, inspired by Jaswant SIngh Khalra’s own words strengthens the filmmakers’ resolve. Honey Trehan stands firm with his film, and declares that he will disown it if the cuts are enforced – it will no longer be my film. “Jaswant Singh Khalra must not be disappeared for the second time,” he says.

Related

Commentaries