Wanted: A Responsible Media in Bihar

On the eve of the polling for the assembly elections in Bihar, veteran journalist Kiran Shaheen* reflects on her four-decade long journey of reporting on Bihar.

Election time again in Bihar! And every election reminds us of innumerable incidents of booth-capturing, murders and the role of the media played in sync with the powers that be. We are also reminded of the brave journalists who tried their best to be on the side of facts and paid the price. There is a long list of journalists subjected to torture, arrest, and even paying with their lives, either during the elections or on so-called ‘normal’ days in the not-so-normal social and political atmosphere of Bihar.

I have been a hard-core civil rights activist-cum-community journalist and later a mainstream media person over a span of almost half a century. Yet, Bihar amazed as much as it horrified me with its entrenched feudalism. I belong to Bihar and Bihar belongs to me. I have been a participant in the mobilizations, campaigns, and movements Bihar has drawn me into, and I have both borne and witnessed injustice, conflict, and the perpetual erosion of human rights.

History of resistance

Dinanath Pande, an 18-year-old youth was killed in police firing in 1954 during what one may call the first student movement of India which originated in Patna’s oldest institution of higher learning, the B N College. Almost 20 years later, Bihar witnessed another mammoth mass upsurge that resulted in the declaration of the State of Emergency during which the government put thousands of protesters, students (including this writer) and several fierce journalists behind the bars. The ink in their pens was forcibly dried, and their voices choked.

At the time, Bihar had only four newspapers. Aryawart (Hindi) and The Indian Nation (English) owned by the King of Darbhanga were more into the change of the power transfer, and the other two, Pradeep (Hindi) and The Searchlight (English) owned by the Birlas, were on the side of the ruling party and vested interests in power.

The newsrooms were all-male and upper-caste, with little thought for ordinary citizens.

In the 1970s, as activists and students we were more accustomed to seeing national reporters on the election ground for the simple reason that despite having ‘so much to talk about what was happening on the ground’, only a handful of staff used to bring out the edition. The news agencies and the local administration were the main sources of news gathering.

At the same time, we used to hear about incidents of caste oppression, land grabbing, destitution of the poor backward caste people and Dalits and sexual oppression of landless women in every nook and corner of Bihar. The state was still reeling under various customary laws considered legitimate and, at times, legal too. Dalits were hardly considered human, and women too were lesser beings.

It was at this time that the famous Jayaprakash Narayan (JP)-led Bihar movement was launched. The process of participation was an awakening for many of us. We left our colleges; seniors burnt their degrees; and the media started opening its eyes to read the writing on the wall. It was a collective learning and as well as unlearning.

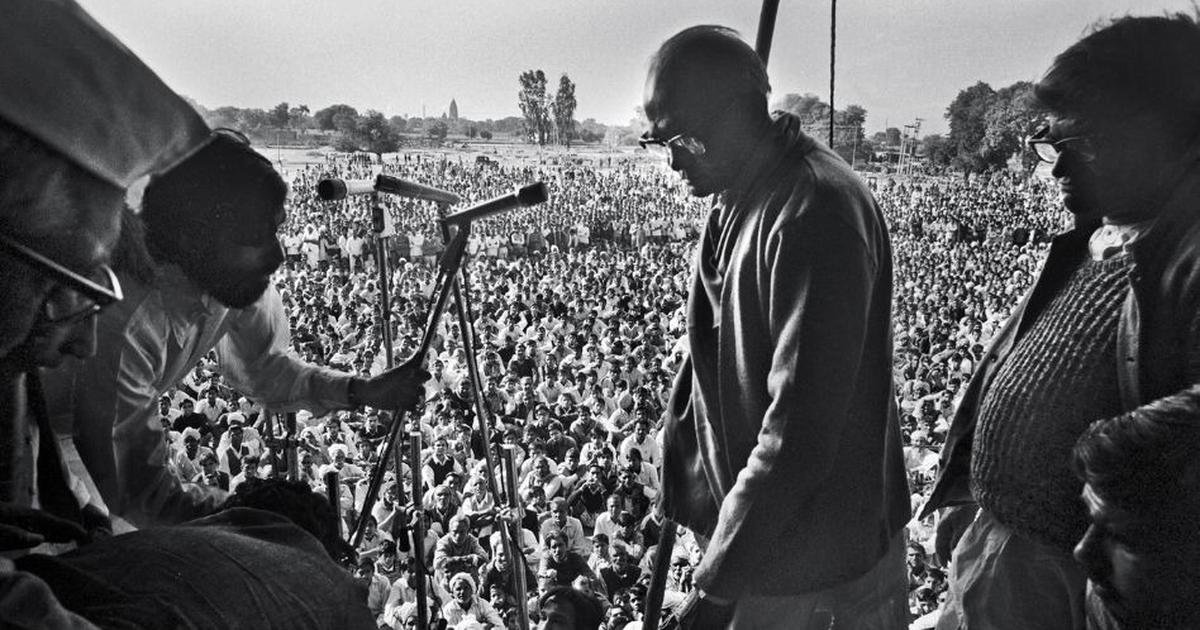

Jayaprakash Narayan at a huge rally at Gandhi Maidan, Patna, 1974. Image Credit: scroll.in

Getting a voice

Despite being an insider in the socio-political arena and the world of journalism for the most part of the past half century, it is still not easy to write about media in Bihar, particularly the coverage of elections and social justice issues. In the 1970s and 80s, on the face of it, journalism was not seemingly divided into pro- and anti-system barracks back then, and we journalists had centre stage to speak our minds. There used to be a subtle pressure from the editor, but of course the editor was also under pressure from politicians and media bosses with vested interests in business and acquiring political power.

I have had the privilege of traveling around with journalists from outside Bihar as a guide and language interpreter even before I became a full-time journalist myself. My work involved provoking someone with a question with a particular reference to caste, or violence or sexual offences, as directed by the journalist. That was something I used to find detestable yet interesting.

When I learnt to read newspapers with a political perspective I could relate to those references and start understanding the intentions behind them more clearly. When I joined a national newspaper’s newly-launched Bihar edition in an unexpected senior position, I found myself in a wonderland where truths were easily twisted and falsehood often found centre space. This process was so subtle that it took me time to understand why news or a viewpoint was not written simply as it was. If I was in charge of a whole page say editorial page or metro page, still the process of choosing news items or perspectives in write ups often would interrupt my ideation about the very profession.

Newspapers in Bihar on November 5, 2025

Still, many of the then new generation of journalists were getting exposure and trying hard to move with the times, particularly after the Bihar movement, lessons of the Emergency, and the emergence of new political leadership minus Congress hegemony. Two significant developments occurred in the 1970s. After the Janata Dal government gave amnesty to thousands of ultra left (Naxalite) prisoners, Central and South Bihar saw a new wave of ultra left movements. Around the same time, with the Mathura rape case opened up by the Supreme Court judgement women’s mobilisation in urban areas created a feminist wave questioning patriarchy in society. We were learning our own pedagogy to say what we wanted to or should have without getting into conflict with our bosses in the editorial and corporate chambers as well. We were not products of a media school; hence, we were learning while doing. Some of us succeeded, while some gave in. On both sides, there was reward and punishment. The choice was ours.

As the history of journalism in Bihar suggests, before the 1980s, there were hardly any newsrooms where women were employed. Even in the later years, very few women were given political beats. This was a period of transition, both in the media and in the society. Owing to the women’s movements in the eighties and nineties, gender justice voices were loud enough to be heard and with a backward caste chief minister (Lalu Prasad Yadav) in place the upper caste boundaries were breaking slowly and steadily. Landless agrarian workers and women too found their voices and their own tools of communications to reach out to masses in the form of small journals and other periodicals.

Police conducted a lathi charge on protesters in Patna during a 1978 demonstration against rising prices. Image Credit: Bihar Digital Archive.

Social injustice at the centre stage

Can you recall how many incidents of political murders, booth capturing, sexual offenses, massacres and treating workers as bonded labour have occurred in Bihar? And how much space and place has been given to them in the media in comparison to the stories about politicians fighting for acquiring more and more power? The media that used to turn its face away from these incidents before, now started feeling the pressure to cover them though in a limited way. Reporters, in their individual capacity, were keen to go into the depth of a news story as a new readership had emerged post-emergency, and issues of social conflict started coming to the fore.

The Bodh Gaya movement in 1978 launched after the Janata Dal government came to power, and ensured that 1500 acres of land was distributed in the first phase in women’s names in 1981. and incidents like the Dalit massacre (1977) in Belchhi where Indira Gandhi, then in opposition, went to extend her support to the victim families are just two examples where journalists in general reacted positively in favour of the oppressed. This period was also a test for their own professional integrity too. Many community-level magazines were brought out by activists and independent journalists, and even by political parties and trade unions that had target audiences in a good number. I fondly call them the ‘social media’ of that era.

Mrs Gandhi’s Belchhi Moment

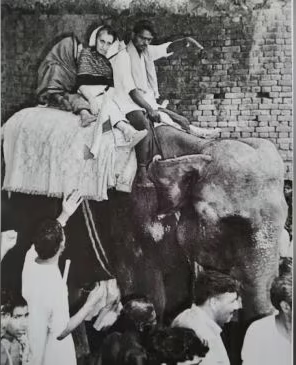

If the media in Bihar has ever covered any news so magnanimously, it was Indira Gandhi’s trip on an elephant to Belchhi, a tiny Dalit hamlet 90 km away from the capital city Patna.

The year was 1977.

Morarji Desai had taken oath as the first non-Congress prime minister of the country. Soon after, Indira Gandhi went into self-exile. And then something happened on 27 May, the day of her father’s death anniversary. Belchhi—a Dalit village near Patna—witnessed a brutal caste massacre where 11 people (eight Dalits and three from backward caste) were shot and burnt alive by Kurmi landlords.

After 78 days of silence, on one rainy day on 13 August 1977, Indira reached Belchhi to offer condolences to the victim families. Though not apparently centred around electoral gain, it was her first step towards the next election. Reporters had queued up to cover her trip riding on an elephant in the muddy water and rains.

Krishna Murari Kishan, a famous photographer who worked with The Indian Nation and Aryawart and with whom I had a close connection as an activist, narrated his experience of covering the incident. When the elephant slipped into a pit due to muddy roads, everyone advised Indira to postpone her plan. They suggested that the victim families could be brought to a Dak Bungalow in the nearby block headquarters. Indira refused this proposal outright and walked through the pits, managing her saree, and reached Belchhi’s aggrieved homes where people had been waiting for her since the morning.

Her gesture was widely praised the next day by newspapers across Bihar and India praising her heroic gesture. It was a turning point in her career, a symbolic act marking her political resurgence. Indira Gandhi’s Belchhi visit had washed the stains of emergency from her political career on the very ground where she had lost her Nehruvian legacy and personal credibility.

Congress was alive again!

Photo of Indira Gandhi riding an elephant to reach the Belchhi village, cut off by monsoon. Image Credit: Photograph by Krishan Murari Kishan (via Bihar Visual Archive).

In the 1970s and 80s, literature saw the ‘Laghu Patrika’ aka small magazine movement, and in the Hindi film Industry, the ‘parallel cinema’ movement, were already getting popular with their specific audiences.

So, the mainstream media also was changing. The incidents of booth capturing or murders/massacres were no longer considered untouchable on the pages of a newspaper. The national press was more alert in the wake of IT revolution and global/glocal phenomenon. The 80s were a turning point with many transformations across the globe and our country as well. The formation of the BJP, the Golden Temple siege, the Assam unrest, Indira Gandhi’s assassination and, in the end of the decade, the Mandal Commission saga and emergence of Lalu Prasad Yadav on the backward caste horizon: all these were eye-opener moments for journalism with the mushrooming of regional newspapers with multiple editions. The newspapers had no option but to meet the growing demand of readers who wanted to read more and more about the ground reality.

Lalu Prasad’s regime brought some forgotten issues to the forefront, the most prominent of them being caste domination. Lalu Prasad challenged it in his own way, and this raised long-awaited concerns in intellectual and media circles.

alu Prasad Yadav. Image Credit: Britannica.

If one goes through the newspapers published during the 1960s to the 1980s, there are numerous reports of the violations of the social justice. At the same time, upper caste private armies with political protection “managed” media that was represented mainly by upper caste journalists, except a few who worked in the national English newspapers and managed to do reporting against these armies. Even when during Lalu Prasad’s regime private armies started losing their grip, the Bihar media was reluctant to bring the social justice issue at the core of the social conflict.

We see the same pattern during the rise of ultra-left movement in rural Bihar where the killing of a private army leader was portrayed as a worsening law and order issue, and the killings by the state or the private army goons were portrayed as a preventive measure to stop left influence among the agrarian workers.

Newspapers with multiple editions had to peep into the social conflict/social justice issues with or without political influence if they had to be part of an emerging news industry. They were not afraid of ‘Doordarshan’ but they already were hearing the footsteps of a TV revolution and had to cope with this unknown danger.

Unfortunately, today we are not in a position to access the old newspapers, specially from Bihar as they have not been digitally archived and many of them shut down. However, our experience as a reader and some of us who entered this profession still recollect memories of the fruitless confrontation with our editors insisting to bring out several painful facts in the light.

In the later years, a significant shift towards TV, digital, and social media campaigning for and against the vested interests with large investments fully changed the scenario. Particularly, in Bihar, the caste-based political influence and feudal supremacy of the big farmers turned politicians have since been dominating the media narrative during the elections.

But with the emergence of the social media, a large army of independent journalists have appeared. Ironically, today, the independent social media journalists are more trusted among the audience than the mainstream corporate-led media. Bihar is no exception, with hundreds of young and senior age journalists bringing the news through their social media platforms that questions the status quo in the political, social and cultural arena. They speak their mind and face the consequences too.

(See the data in the FSC Report.)

Polls and the media in Bihar

The upcoming assembly elections in Bihar to be held on 6 November and 11 November 2025 has triggered a boom in political advertising. On the one hand, government advertisements are pouring in, making media a natural beneficiary that is bound to protect advertisers’ political interests. And on the other hand, most contesting parties are spending huge money on digital advertising as part of their online campaigns, while also partnering with social media influencers to deliver their messages and build a favourable atmosphere.

As I write these lines towards the end of 2025, going through a few newspapers from Bihar on the net was heart-breaking. Most of the newspapers are filled with shallow political news clippings and hardly talk about the real issues pertaining to this election. They talk about women as fodder to the election machine; they talk about the landless migrant workers in the most non-serious manner. No newspaper mentions that the working-class voter is still getting wages below the legally sanctioned wage. They do not talk about how people who are alive but shown dead in the final list of the Election Commission will cast their vote. Almost all TV channels, even YouTubers and newspapers are pushing and shoving each other to interview a powerful politician or are adamant to make them fight with each other. Every dialogue is crafted. Every scene is staged. The whole masala film!

Amid this ruckus, a small percentage of journalists—independent, staff or YouTubers—is raising issues that touch everyday lives of common people across the state in this crucial juncture of political history of Bihar. I always say that mainstream is not what a capitalist throws in the market but what our ordinary citizens are creating in their hutments and their villages.

The mainstream flows from there.

*About Kiran Shaheen: A longtime gender justice activist and journalist from Bihar, Kiran Shaheen has worked with several prominent Hindi and English media, including Navbharat Times, BITV, BBC with their Home TV venture and Nai Duniya. She edited and published ‘Apni Azadi ke liye’ a feminist community newspaper.

Read our special features:

The “Deletion” of Independent Journalism: Bihar’s Free Speech Record, November ‘20-’25 (An FSC Report)

Criminalisation of politics in Bihar, by C P Jha

Related

Commentaries