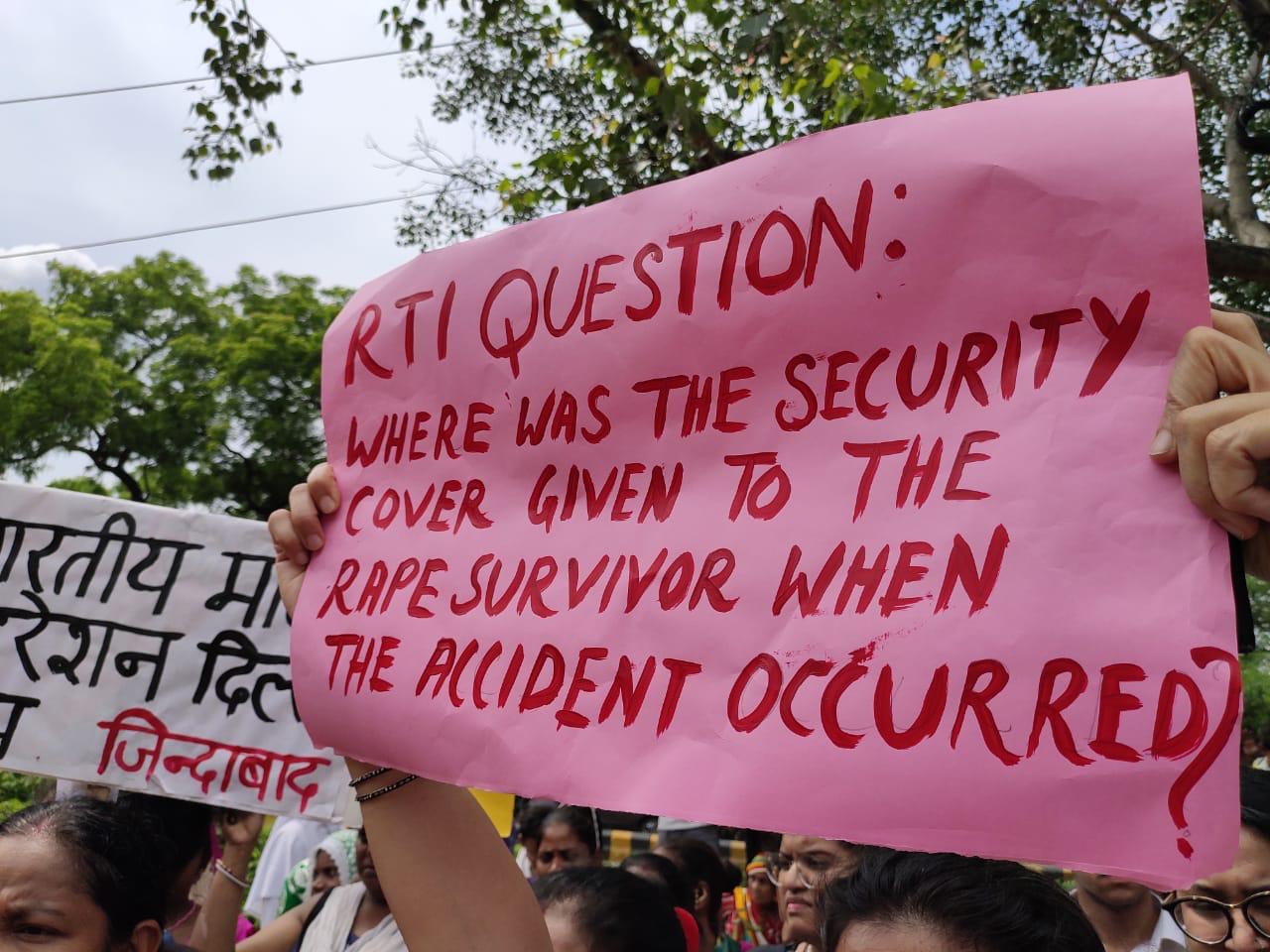

Eighty-four appellants demanding information under the Right to Information Act (RTI) have so far been killed in India, and the perpetrators of these murders have yet to be brought to justice. Now, the Modi government has dealt an unmistakable blow to the autonomy of information commissioners, thereby ending all pretence of transparent governance.

By Sohini C

On 31July 2019, the Modi government amended the Right to Information Act passed in 2005, with the final signature of approval coming from a man who had helped strengthen it when it was formulated—President Ramnath Kovind. The amendment significantly reduces the powers of Information Commissioners, who were earlier elected for a period of five years from the date of appointment, and given a salary on par with election commissioners, officers whose independence was conceived as sacrosanct to ensure free and fair elections. The new Bill says the tenure and salary of the Information Commissionerswill be “prescribed” by the Central government.

“This is an ‘amendment’ that achieves nothing in terms of making the RTI better, it only compromises the autonomy of the information commissioners,” said Shailesh Gandhi, former chief information commissioner and one of the most vocal activists of the right to information. “Information commissioners, before this amendment, were on par with Supreme Court judges and Election Commissioners and you could not challenge their orders by appealing in court. Now, they will be under the Central government.”

Interestingly, in 2005, President Kovind was on a Parliamentary Committee that had argued that information commissioners must be given a position higher than secretaries, which was the original rank allotted to them, so that their decisions could have autonomy from their political bosses. The BJP had, in fact, substantively used the RTI during the time of the UPA government to bolster their charges of corruption.

In truth, the Right to Information Act has been comatose for several years now. It has potential to be India’s most powerful democratic right, the right to ask government and its officers questions about decisions, to demand accountability and transparency. It was the best Constitutional check against corruption—one of the issues which propelled the Modi government to power—because the Act empowered citizens to ask public officials to furnish documents and accounts on expenditure among other things.

For me, a health reporter, the RTI Act offered the only route to secure data on surgeries and medical procedures and treatments because the hospitals (mis)use the confidentiality clause that protects the privacy of patients to deny data on questions of public interest such as percentage of Caesarean sections performed in a year, or the number of women who are living organ donors in organ transplant surgeries. Every government department is supposed to list the names of the officers designated to respond to right to information appeals, and some do so on their websites. The right also came with an impressive promise for India’s lethargic bureaucracy—that the information sought would be provided within a period of 30 days.

It testifies to the Act’s potency that 84 RTI users have been murdered in India so far, according to database maintained by the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative. Another seven persons have been driven to suicide, and there have been 169 assaults that can be related to seeking information under the RTI. But this might has waned in recent years, with the infamous bureaucracy and wily state choking it to a comatose state.

More recently, Maharashtra has started responding to RTI queries only in Marathi, which means I have to request a Marathi reader to read out the replies to me which is possible but extremely time-consuming. There have been instances when departments have not responded at all to a request and when I followed up to seek a reply, they backdated their answers to meet the 30-day deadline. There are other logistical issues as well—even when you receive an approval for a document sought, there is no guarantee that the staff of the office will provide it. They hold out for a bribe. The solution to this is simple—the RTI officer concerned should send the document to the appellant following the payment of a fee.

The existing state of affairs remained largely unknown, although RTI users, some of them dogged enough to be called activists, complained. But it was seen as business as usual, the standard lethargy and opacity of the Indian bureaucracy, to merit attention in the public domain.Be patient, this is India, and you can appeal if you don’t get a response, people would tell me. But this is the rub—the bureaucracy had been choking the Act by delay tactics, frustrating appellants and tiring them out. It is during this long wait, when some appellants asking inconvenient questions have been threatened and assaulted, and when it is clear that they will not back down, bumped off.

The Modi government’s savage attack on the Act brings to light how vital the right to information is, and how inconvenient it feels to the powers that be. This week, when RTI activists took a petition signed by several thousand persons online to President Kovind to request him not to sign this amendment into law, they were stopped by police outside the Rashtrapati Bhawan and activist Anjali Bhardwaj detained.

The pretence at least is over: India’s so-called democratically-elected government will brook no questions. I shall no longer hold my breath when I file half a dozen requests for one public document. I won’t nod when well-meaning people tell me to have faith in the messy, lengthy democratic process. For that, we must all be thankful to Prime Minister Modi.

Sohini C is an independent journalist and writer based in Kolkata