A Free Speech Collective Report, December 2025

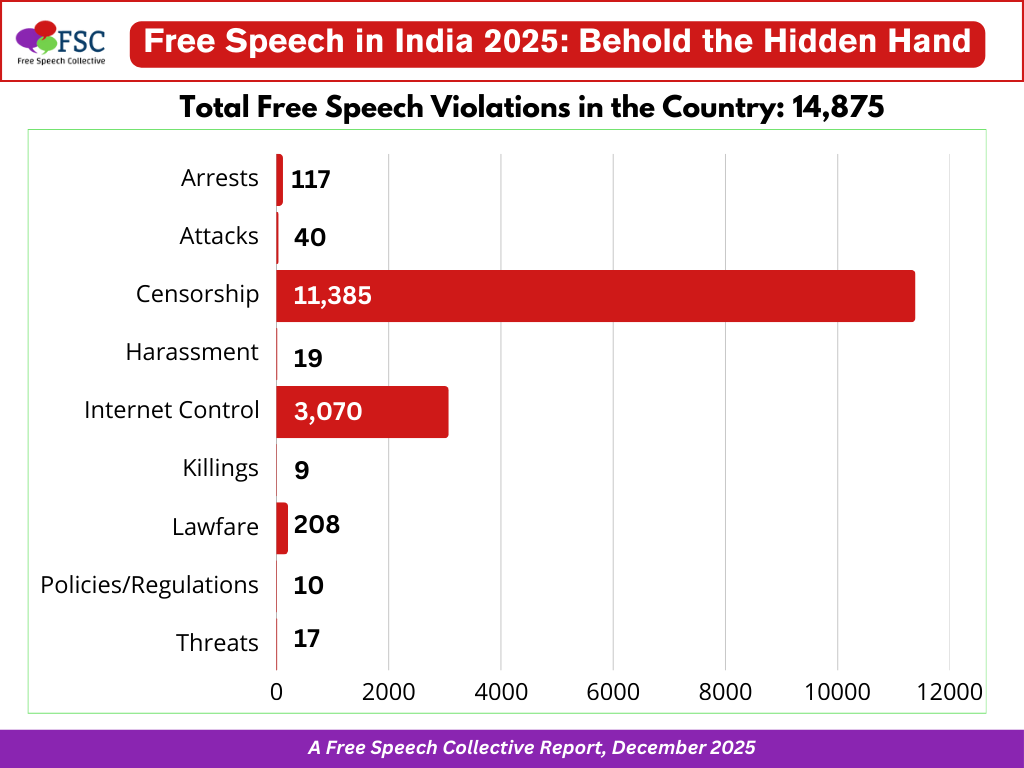

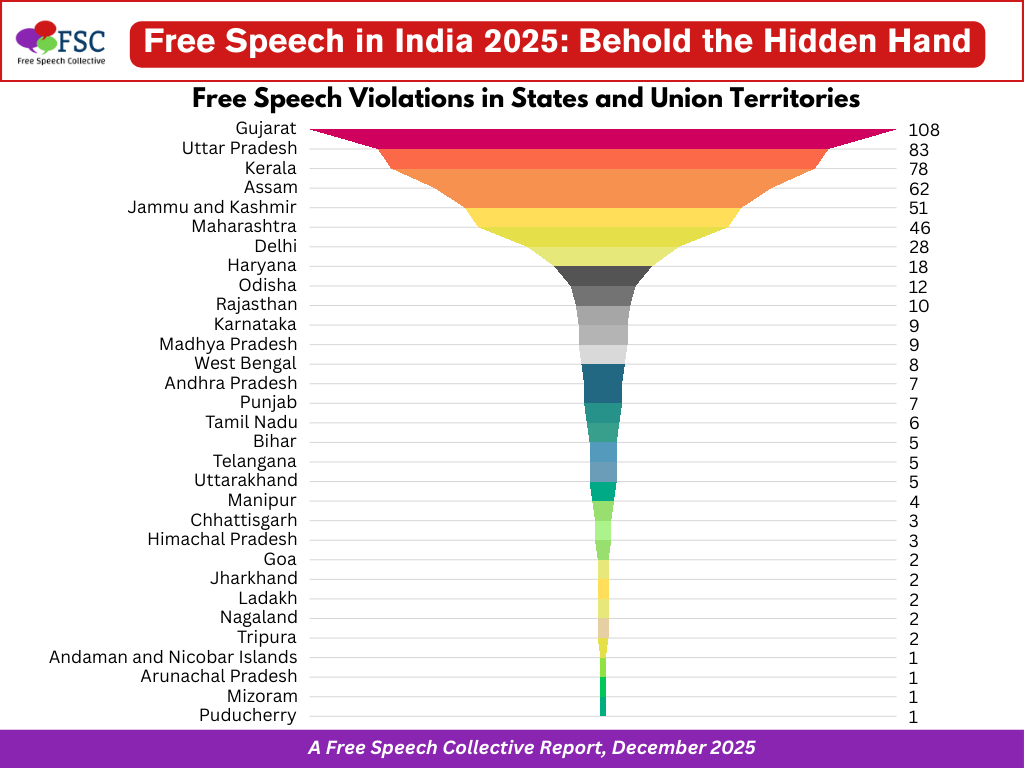

The ominous start to 2025, with the reported disappearance of journalist Mukesh Chandrakar days after he reported on the poor quality of road construction and the chilling discovery of his body in a septic tank in Bastar on January 3, marked an alarming disintegration of free speech protection in India. A staggering 14,875 instances of free speech violations were recorded through the year, including nine killings – of eight journalists and one social media influencer, 117 arrests of citizens, including eight journalists and an unprecedented 11,385 instances of censorship and 208 of lawfare signifying “mass” censorship and criminal cases lodged against multiple persons.

While India’s dismal record of freedom of expression in the last decade is not new, granular data recorded by Free Speech Collective (FSC) illustrates how the spike in figures of censorship and internet control has rendered all citizens vulnerable. This is in addition to the data recorded by the Free Speech Tracker in other categories of free speech violation—from deaths, attacks, and law fare including arrests to censorship in news, cinema, literature, and academia, as well as government policies and laws that regulate the free flow of information.

The censorship figures recorded by the (FSC) tracker include the mass requests by the Indian government to withhold over 8000 accounts on ‘X’ in India in May and another 2354 accounts in July. While specific details of all the accounts for which access was withheld in India are not available in the public domain, the figures could be higher, gauging from the submission made by ‘X’ to the Karnataka High Court in its challenge to the Sahyog portal, where it stated that it received 29,118 government requests to remove content between January and June 2025 and complied with 26,641 of them). Other instances of internet control amounted to 3070, including shutdowns, blocking of apps and the 785 blocking orders issued by the I.T. Ministry to various online intermediaries in the months of January and February 2025.

The past year saw the speedy roll out of restrictive legal and regulatory policies ostensibly to protect data privacy. But it was the deployment of various arms of the state to issue arbitrary orders of censorship that underscored the inexorable march towards a majoritarian state that viewed independent enquiry and dissent as “anti-national” acts. While self-censorship increased, the hidden hand directing it, both informally as well as through institutional mechanisms and the openly powerful attempts by big corporates to control media narratives, became more evident in 2025.

India’s ranking in various global press freedom indices has been in free fall for several years. The downslide continued in 2025. There were 40 attacks of which 33 were on journalists. At least 14 of the 19 instances of harassment and 12 of the 17 threats were recorded against journalists doing their professional work. The threat issued by Telugu Desam Party (TDP) MLA, Gummanur Jayaram, to make reporters sleep on train tracks if they published “false” information on him, typified the dismissive attitude of elected representatives towards journalists.

Journalists working in rural districts bore the brunt of the direct physical attacks for their stories on local corruption, maladministration and illegal activities. Police routinely attributed the killing to motives other than their journalistic work and it was only pushbacks from their colleagues forced police investigations. For example, the body of journalist Mukesh Chandrakar was found in a septic tank, only after the insistence of his colleagues for a thorough search of the premises. In another instance, the body of Rajeev Pratap, who ran a YouTube channel Delhi Uttarakhand Live, was found in the Bhagirathi river and his car found upstream, days after he aired a video on liquor consumption in a local hospital. Police claimed that Pratap was drunk and had driven off the road into the river.

Two journalists, Irfan Mehraj of Kashmir and Rupesh Kumar of Jharkhand, continue to languish in jail since March 2023 and July 2022, respectively, charged under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. Apart from media persons, attacks on citizens exercising their right to freedom of expression included the manhandling of pro-Palestine protestors in Pune and the disruption of a Peoples’ Tribunal press conference in Delhi, both by Hindutva mobs and the attack on lawyer and civil liberties activist V Suresh by the mining mafia during a People’s Tribunal hearing on illegal mineral quarrying in Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu.

In April, the colonial-era sedition law made a comeback in a new avatar, less than a year after the new criminal codes were notified. Satirists Neha Singh Rathore, Madri Kakoti (a.k.a. Dr Medusa) and Shamita Yadav (a.k.a. Ranting Gola) were charged with sedition for their posts online questioning administrative and intelligence failures in connection with the Pahalgam attack. On December 5, in a marked departure from a more accommodating approach, the Allahabad High Court rejected Rathore’s anticipatory bail plea, maintaining that her tweets were disrespectful and did not merit any pre-trial protection.

In August, Assam police registered an FIR under sedition citing articles published in The Wire by at least 12 columnists in the wake of the Pahalgam attack, against the founding editor of The Wire Siddharth Varadarajan, consulting editor Karan Thapar, Satyapal Mallik (ex-governor of J&K and Meghalaya, who had passed away earlier in the month), Najam Sethi (journalist and former Caretaker Chief Minister of Punjab in Pakistan), and Ashutosh Bhardwaj (Editor of The Wire Hindi).

In August, journalist Abhisar Sarma was charged with sedition by Assam police for his show on YouTube. In his tweet, Sarma said the FIR filed against him was “completely baseless” and he had mentioned the statement of an Assam judge on the controversial land deal given to Mahabal Cement by Assam government as well as “highlighted Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s communal politics with facts — based on his own statement”.

In March, a comedy club venue in Mumbai was vandalised over a joke about Maharashtra’s Deputy Chief Minister Eknath Shinde recorded at the venue by stand-up comedian Kunal Kamra. Kamra was charged with criminal defamation and summons were issued for his arrest. In April, the Bombay High Court granted him protection from arrest but, in June, the Maharashtra Legislative Council admitted a breach of privilege motion against him.

In another instance of breach of privilege, the Privileges Committee of the Maharashtra Legislative Council recommended a five day jail sentence to four journalists – Ganesh Sonone, Harshada Sonone, Amol Nandurkar and Satish Deshmukh, the editor of YouTube channel Satya Ladha and a local Congress volunteer Ankush Gawande, for allegedly defaming NCP (Ajit Pawar) MLC Amol Mitkari. Deshmukh was later let off after he submitted an apology. However, the report on YouTube channel Satya Ladha has been taken down.

Censorship: Backdoor Institutional Regulation and The Hidden Hand

Censorship has long been the new normal in India. News reports and YouTube news channels like Knocking News, run by veteran journalist Girijesh Vashistha were taken down. In November 2025, a raid was conducted on the offices of the Kashmir Times in Jammu by the State Investigation Agency (SIA) of the Jammu & Kashmir Police to investigate its alleged activities inimical to the country. In a statement, Kashmir Times, which was founded in 1954, said that this was another attempt to silence “one of the few independent outlets willing to speak truth to power”. The Reporter’s Collective, an investigative news portal, found its non-profit, tax-exempt status revoked by the government on grounds that it was not in the public interest. The decision, which is under challenge, has crippled its financial strength and restricted its work.

While censorship has intensified in almost every sphere, newer forms of institutional mechanisms of regulation have been unveiled this year. The Sahyog portal, which empowered a host of state agencies, district-level officers and the local police to issue takedown notices to social media platform, blocked scores of accounts. On May 8, in the wake of the Pahalgam attack on April 22, X’s Global Government Affairs Team announced that the platform had to block over 8000 accounts, without obtaining any evidence or justification or which posts had violated the law in India.

The ‘X’ accounts of news portals The Wire and Maktoob Media, Kashmir Times editor Anuradha Bhasin, Indian Express Deputy Editor Muzameel Jaleel, political content creator Arpit Sharma, Reuters, and others were withheld in India.

On September 24, 2025 a single-judge bench of the Karnataka High Court rejected X’s challenge against the portal. In its 351-page judgment, the Court upheld the Sahyog portal as “an instrument of public good” and reiterated that online expression is “hedged by restrictions.”

An RTI filed by Al Jazeera said that Indian government officials had sought the removal of 3,465 URLs in India, 294 takedowns from October 2024-June 2025; 25 notices and 87 URLs between October-December 2024; 269 takedowns and 3,276 URLs from January to June 2025.

Self-censorship by media organisations and unofficial directives by government officials to set the news agenda, long whispered about in the corridors of power, also broke the shroud of silence this year. The alleged removal of Hiren Joshi, Modi’s officer on special duty who is widely believed to be helming the PM’s communication strategy, from his post, spawned a number of reports on his daily calls to media houses, including the mysterious take down of a report on the issue in The Print news portal.

There was, hitherto, little formal corroboration of the unofficial methods used by law enforcement agencies to intimidate media organisations by way of verbal summons or “friendly” calls. Journalists are also wary of disclosing these attempts, unless backed by strong support from their media organisations, as in the latest instance when news site The Wire issued a statement condemning the Jammu and Kashmir police seizure of the mobile phone of their correspondent Jehangir Ali on December 17, 2025. Ali had been working on an investigative report on allegations of nepotism and corruption in the Ratle hydro power project in Kishtwar at the time.

Senior journalist and editor Patricia Mukhim announced in a post on her Facebook account that she stopped her column in Assam Tribune as her article entitled ‘Needed a political catharsis’ on the plight of the Muslim community who were being targeted by an eviction drive in Assam was denied publication.

Gag Orders and Corporate Muscle

In an unprecedented move, both big corporations and the government joined hands to protect the former’s interests. On September 16, 2025, corporate giant Adani a Delhi civil court issued an ex-parte injunction restraining nine journalists and news platforms (including journalists Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and Ravi Nair and news platforms like Newslaundry and The Wire) from publishing allegedly “defamatory” content against Adani Enterprises Limited (AEL).

The court ordered the immediate takedown of 138 YouTube videos and over 80 Instagram posts from prominent news outlets and commentators and the Union Ministry for Information and Broadcasting (MIB) followed swiftly with takedown notices. On September 18, a Delhi lower court removed the order stating that it was unsustainable.

In another development regarding the Vantara zoo run by Anant Ambani of Reliance Industries, multiple attempts were made to curb coverage of the manner in which the private zoo had acquired endangered animals from across the world, many of them being endangered species. In May, the Delhi High Court on 19 May 2025 dismissed a contempt petition against Himal Southasian and its editor, filed by Greens Zoological, Rescue and Rehabilitation Centre (GZRRC) and the Radhe Krishna Temple Elephant Welfare Trust, parts of Vantara. The latter had alleged that Himal wilfully disobeyed a judicial order to take down an investigative story on the wildlife project published on the Himal website in March 2024.

But the Delhi High Court held that there was no judicial order or direction passed by the Court against Himal requiring the magazine to remove the story and the issue of contempt did not arise. In the same vein, a revelation uncovered that a fake law firm even used the identity of a well-known lawyer and sought to gag independent and critical journalists and media outlets. However, media houses continued to play safe and removed their stories on Vantara.

Gag orders on media coverage sought “mass” restraints on cases as varied as the Dharmasthala mass burial case, wherein a Karnataka lower court ordered the removal of 8800 news links and restrained 338 respondents from publishing any proceedings related to the case. The order was later struck down by the Karnataka High Court.

Crushing Academic Autonomy

With at least 16 serious instances of censorship in academia, the atmosphere for free enquiry within university portals remained stifling. While student protests were criminalised, there were open prescriptions by University Vice Chancellors exhorting faculty to align with the majoritarian political ideology of the ruling BJP and attacks on the teaching of history by so-called “propagandists” pushing a “Nehruvian consensus” and attempts to change curriculum. As the “Free to Think” Report of the Scholars at Risk Academic Freedom Monitoring Project, 2025, stated, “the central government, led by the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), took actions to extend its authority over the country’s system of higher education, undermining university autonomy.”

Permissions were denied or academic conferences cancelled and stringent regulations governed the freedom of academics to host, speak or even attend national or international seminars without prior clearance.

As in the past years, visiting academics continued to find it difficult to obtain visas to travel to India and when they did, they were deported on landing in the country. In October, the UK-based Francesca Orsini, well known for her scholarly work on Hindi and Professor Emerita at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), were deported without any reason given.

The Indian government cancelled the Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) status of UK-based academic Nitasha Kaul, citing her alleged “anti-India activities”. Kaul, who is also a Kashmiri Pandit, had testified against the Indian government at the US House Committee on Foreign Affairs over “human rights violations” in Kashmir in 2019 and was deported from Bengaluru airport in February 2024. In November this year, she challenged the revocation of her OCI status.

In Kashmir, in an unprecedented order in August, the Jammu and Kashmir Home department banned 25 scholarly books on the history and politics of Kashmir, written by respected scholars like A G Noorani and Christopher Snedden, Angana Chatterjee, writer Arundhati Roy, activists and lawyers Subsequently, Kashmir police raided bookstores and seized books on Islam published by New Delhi-based Markazi Maktaba Islami Publishers.

In another development that signalled the privileging of copyright protection for commercial academic publishers, Delhi High Court banned shadow library sites Sci-Hub and Sci-Net through Internet Service Providers (ISPs) in August 2025, despite efforts by researchers and students that the move would hamper free and affordable access to information.

Film Censorship: From the Absurd to the Ridiculous

The untrammelled use of certification as a tool of censorship, descended from the absurd to the ridiculous. In December 2025, the Union Ministry of Information and Broadcasting denied the International Film Festival of Kerala permission to screen 19 films, including the classic Battleship Potemkin, a hundred years after it was made. Earlier, certification officers, fearful of the reaction of Hindutva mobs, objected to the use of the word “Beef” (though it had nothing to do with cow slaughter) or “Janaki” (the story of a rape victim called Janaki, which is another name for Sita, the wife of Hindu deity Ram) in film titles and granted certification only after enforcing cuts in vital scenes.

Film maker Neeraj Ghaywan’s “Homebound,” on the moving relationship between two friends who decided to walk home during the lockdown due to the Covid-19 pandemic, was allowed certification only after 11 cuts.

While several film-makers succumbed to the cuts, orders for extensive cuts (over 120) and inordinate delay in grant of certification amounted to a virtual ban on the release of films like Punjab 65, based on the life of human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalra and starring singer-actor Diljit Dosanj. Given “invisible” pressures, mounting a legal battle to challenge the CBFC, as film maker Honey Trehan said in this interview, proved impossible.

The award-winning internationally-produced film Santosh by British filmmaker Sandhya Suri, which was the U.K.’s official Oscar’s submission last year, could not be released in India because it was denied a CBFC certificate. The film dealt with the rape and murder of a Dalit girl and police cover-up of powerful perpetrators of the crime.

The invisible hand made its appearance even with the video review of the film Dhurandhar by senior film critic and the Editor of The Hollywood Reporter India, Anupama Chopra, was made private after a backlash and abuse from trolls and a few actors from the Hindi film industry. In February, YouTuber Ranveer Allahbadia, charged with obscenity for making sexually explicit comments in a podcast, was restrained from posting any content on social media.

When CBFC Watch, an open-source database that recorded decisions of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) from 2017 to 2025, put out its documentation of more than 100,000 cuts made to nearly 20,000 films over the last seven years, the CBFC quickly updated its e-Cinepramaan portal and restricted public access to film certification details and cut lists.

Over Regulation to Tackle Cyber Crime and Protect Privacy

The rolling out of laws like the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023 struck the death knell for independent news gathering and information in the name of data protection. The Rules for the act, notified in November 2025, classified reporters and media organisations as “data fiduciaries’ while a crucial amendment to Section 8(1)(j) of the RTI Act removed the provision for exemption in the “public interest”. The rules, taken together, potentially threaten source confidentiality and impose impractical consent requirements for newsgathering. The penalties for violation of provisions of the act can go up to Rs 250 Crore. The DIGIPUB News India Foundation issued a strong statement against the restrictive Rules, saying that the framework “endangers journalism” and weakens India’s transparency regime by diluting the Right to Information Act.

Other attempts to constantly reinforce the invisible regulatory hand came in the form of an advisory in December 2025, by the Union Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) to VPNs to block access to websites that allegedly unlawfully expose citizens’ data. Notably, these service providers do not log user information, and several top VPNs removed physical servers from India after directives to store user data to be shared with investigative authorities upon request. Earlier in April-May 2025, amidst border tensions with Pakistan following ‘Operation Sindoor’ in the aftermath of the terror attack in Pahalgam, MeitY ordered takedown of over 3,000 apps from Google Play Store. The broad ban targeted VPNs, religious apps, streaming services, AI tools, and even utilities like calculators.

Privacy rights and the right to information in the public interest continued to be at loggerheads. A spate of ad interim injunctions in favour of celebrities reaffirmed “personality rights” but there were fears that an overemphasis on celebrity/publicity rights could not infringe on constitutionally protected forms of expression.

Judicial flipflops

The judiciary, considered the last bastion to protect free speech, remained inconsistent in protections granted to citizens. While a few orders upheld freedom of expression, as in the Supreme Court judgement by Justice Abhay Oka and Ujjwal Bhuyan which quashed an FIR filed against MP Imran Pratapgarhi for reciting an Urdu poem that allegedly promoted enmity between communities, stating that Courts are duty-bound to protect “poetry, dramas, films, stage shows including stand-up comedy, satire and art,” as they make the “lives of human beings more meaningful.”

But in another order, granting interim bail to Ashoka University Professor Ali Khan Mahmudabad, the Supreme Court Bench of Justices Surya Kant and N K Singh directed a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to interpret the “hidden meaning” behind Mahmudabad’s posts and laid down bail conditions gagging the professor from speaking about Operation Sindoor.

If some sections of the judiciary displayed a more paternalistic attitude, as in the case of the film Thug Life, where the Karnataka High Court stopped the release of the film and demanded an apology from the actor Kamal Hasan for allegedly denigrating Kannada, it took the Supreme Court to order the release of the CBFC-cleared film and state that the High Court had “no business to seek regret or apology”.

Regulatory Policies: More Censorship in the Offing

In December, the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) issued a directive mandating the continuous SIM–device binding, already in use in banking and UPI, for communication app-based messaging platforms like WhatsApp, Telegram and Signal, to prevent cyber fraud. The mandating of a mobile number as a user identifier to ensure continued access and has raised concerns about privacy and increased surveillance.

Internet freedom activists pointed out the perils of directives mandating the installation of the Sanchar Saathi app on all mobile devices (a move that was made voluntary after protests). Lawyers also flagged new definition of “synthetically generated information”, ostensibly to deal with deepfakes, in the draft amendment to the IT Rules, 2021 (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Amendment Rules, 2025. The sweeping and general provisions in the draft, which was open to consultations till November 13, 2025, could potentially curb or restrict all AI-generated content.

The prospects for free speech in the coming year looks even grimmer as the muscular state pushes increasingly restrictive regulatory mechanisms, with the active support of big corporates, both as owners of big media and as influencers of social media narratives. The intensification of the crackdown on independent voices of dissent and the crippling of independent media platforms will only serve to further pollute the climate for the free flow of information, stifling the right to think and express freely.

Note: A PDF version of the report can be downloaded here.

Browse the Free Speech Tracker Database: The Free Speech Tracker is a database that records free speech violations in India across various categories. Tracked violations can be searched across categories, states, and/or years.