Prabir Purkayastha, founder editor of the news portal, ‘Newsclick’, was arrested on Oct 4, 2023, under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967, along with the Human Resources head of the company, Amit Chakrabarty, after Delhi police raided more than 30 journalists in New Delhi, Mumbai and Chennai. The raids and the arrest followed the publication of a New York Times report alleging that the news portal had received funding to publish Chinese propaganda.

The 75 year old Purkayastha, who had been arrested in 1975 during the Emergency, is an engineer, activist for pro people science and technology and is President of the Free Software Movement of India.

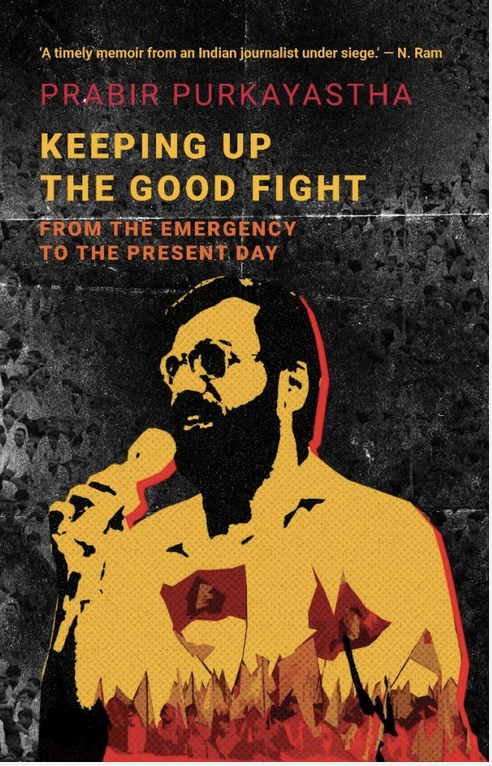

In this excerpt from his autobiography, “Keeping Up the Good Fight: From the Emergency to the Present Day”, he talks about the new censors of today:

My earlier ‘emergency encounter’ was in the context of the students’ resistance in JNU. D.P. Tripathi, Ashoklata (usually called Ashoka), Sitaram (Yechury) and others were among the key figures in that resistance.

My encounter in the current ‘emergency’ took place in rather different circumstances. NewsClick, a relatively small outfit, was somehow perceived to be a ‘problem’. Perhaps the problem was not so much NewsClick as the range of movements it covers. Just prior to the government’s unwelcome attention, NewsClick had covered the farmers’ movement quite thoroughly, coverage that drew significant viewership, and not just in India.

But then again, NewsClick was not, and is not, unique in its coverage. Many other digital platforms, and even certain mainstream media, have covered assaults on people, livelihood and reason, as well as the public protests that take place in response. Like us, some of these media organisations are very much under the Government’s scanner.

I do not want to go into the various cases that NewsClick and I continue to face; or the campaign unleashed against us by a hounding variety of media. The legal matters are in the courts and we will fight the cases there. I have no desire to become the news. Nor does NewsClick; its job is to cover the news. It will continue to do what it has done from the time it was set up: follow people’s movements on the ground and amplify the voices of those who are rarely heard in our society.

For many years now, I have taken part in an annual ritual in the month of June — of looking back to when democracy was last in a state of suspension. The Emergency was declared on June 25, 1975, and remained in effect till March 21, 1977. The intervening 21 months made up a grim period in India’s post-independence history. There were widespread arrests and ‘preventive detention’ of the opposition, from political leaders to students. Protest and dissent were crushed, the media was censored, and there was fear in the air, a sense of persecution and paranoia. In short, fundamental rights were curtailed to the extent that they seemed, in these months, absent.

This development was all the more shocking because till the Emergency, India was proud of the fact that it was a democracy — the reigning cliché of the time, world’s largest democracy, remains much in use — and was also proud of the fact that it had become a democracy immediately after independence in 1947.

It was as if, in one stroke, dissent, free speech and all the other characteristics of a democracy could be struck down by the administrative machinery of the state. . . .

. . . . Undoubtedly, the 1975 Emergency was an acid test for many sections. The media, the bureaucracy and a number of political parties and personalities were found wanting. The highest judiciary in the country, the Supreme Court, failed to show even the courage the High Courts did, sanctioning the formal butchery of our fundamental rights to life, liberty and free speech.

But for many others, the Emergency was also a time to assert their beliefs. Some resisted quietly, out of the public eye. Others expressed their opposition more visibly. For the generation born after the freedom struggle, this was arguably the first big political test. While the people, the Indian citizenry in general, passed this test, the same cannot be said of some of the more elite sections and bourgeois institutions.

The Indian people are quite often mistaken to be passive. They do not rise up in revolt periodically against the terrible burden of oppression that they carry; this is a criticism commonly levelled against them. Yet, this mass of ‘passive’ people routed Mrs Gandhi in 1977 and asserted the primacy of Indian democracy. This forced Mrs Gandhi to apologise to the people for the Emergency. Some have argued that if the verdict of 1977 was so unambiguous, how is it that the same people voted her back to power in 1980? The answer lies in the confidence that the people had acquired in 1977. They had taught Mrs Gandhi a lesson they were sure she was not going to forget. And to their credit, they were proved right — Mrs Gandhi did not re-impose an authoritarian regime.

But to get back to the question of then and now: To begin with, it appears that an ‘emergency’ — as a general description of repression — is a destructive situation that develops if the political dispensation of the time erodes people’s fundamental rights in numerous ways. This is one way to frame the similarities between then and now. But with each point of ‘similarity’, there are differences as well. Some are rather stark, such as that of the ideology driving the attack on citizens’ rights in the present.

Some of the differences are, perhaps, more nuanced — in, for example, the ways in which authoritarianism is expressed.

Let me, as a ‘midnight’s child’, consider the situation in India today, not just keeping in mind the 1975 Emergency to compare two aberrant periods, but also keeping in mind the larger context of 75 years of the secular, diverse, democratic, constitution-guided republic of India.

THE MEDIA THEN AND NOW

Among the most enduring memories of the Emergency (other than enforced vasectomies) are those of a scared, docile press. The administration had powers to muzzle the media — what the press wrote had to be submitted to censors. Everyone recalls L.K. Advani’s chastising remark to the press after the Emergency: ‘You were asked only to bend, but you crawled.’

But we also have to remember and salute honourable exceptions that didn’t bow down, or carry government propaganda. The Indian Express managed to operate within the new constraints. Its blank editorial was a powerful symbol of protest against the attack on the role of the fourth estate. Smaller organisations also resisted the bully censor; for instance, the journal Seminar run by Romesh Thapar. Of course, what they could do was necessarily limited.

How does the Indian media scene today compare with those times? Media then meant mainly the print medium — the ‘press’. We have a number of platforms today, and it’s certainly much harder to control them all.The media is much more heterogeneous; and the agenda for media has been set differently. Earlier, print media set what made news. The headline of the day would determine what the news was. Now that we have 24×7 news channels on television, the news has changed. Watching prime-time news ‘debates’ can give us a preview of the news cycle.

Social media has completely changed the landscape of what was earlier considered news or commentary, and so also with the influence and reach of media. Social media even sets the news now — what issues will be discussed and commented upon by both journalists and readers. This is, obviously, much more difficult to control. Which is why, despite the best efforts of the BJP and Modi acolytes, you do hear other voices.

Of course, the government and its cohorts are anxious to control the large number of individuals using social media; to do this, they have to come up with measures different from what sufficed during the earlier Emergency.

In other words, a technological change has taken place which makes the task of muzzling the press rather different from what it used to be. If you want to muzzle a million or more people, you cannot use the Emergency instrument, which was direct censorship.

What are the new censors — official and unofficial —to do?

They make an example of a few to create a chilling effect. They make people afraid; self-censorship becomes the norm. They make use of continuous harassment, by filing FIRs all over the country; what used to be called lawfare in other jurisdictions. Remember the case of the artist M.F. Husain? Cases were filed against him practically everywhere. Criminal proceedings were initiated against him for allegedly hurting public sentiment with his paintings. Groups such as the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and the Bajrang Dal issued threats against the 90-year-old painter. Finally, unable to take it anymore, Husain left the country and lived in self-exile till his death.

Extracted with permission from “Keeping Up the Good Fight: From the Emergency to the Present Day” by Prabir Purkayastha, LeftWord Books, New Delhi, 2023